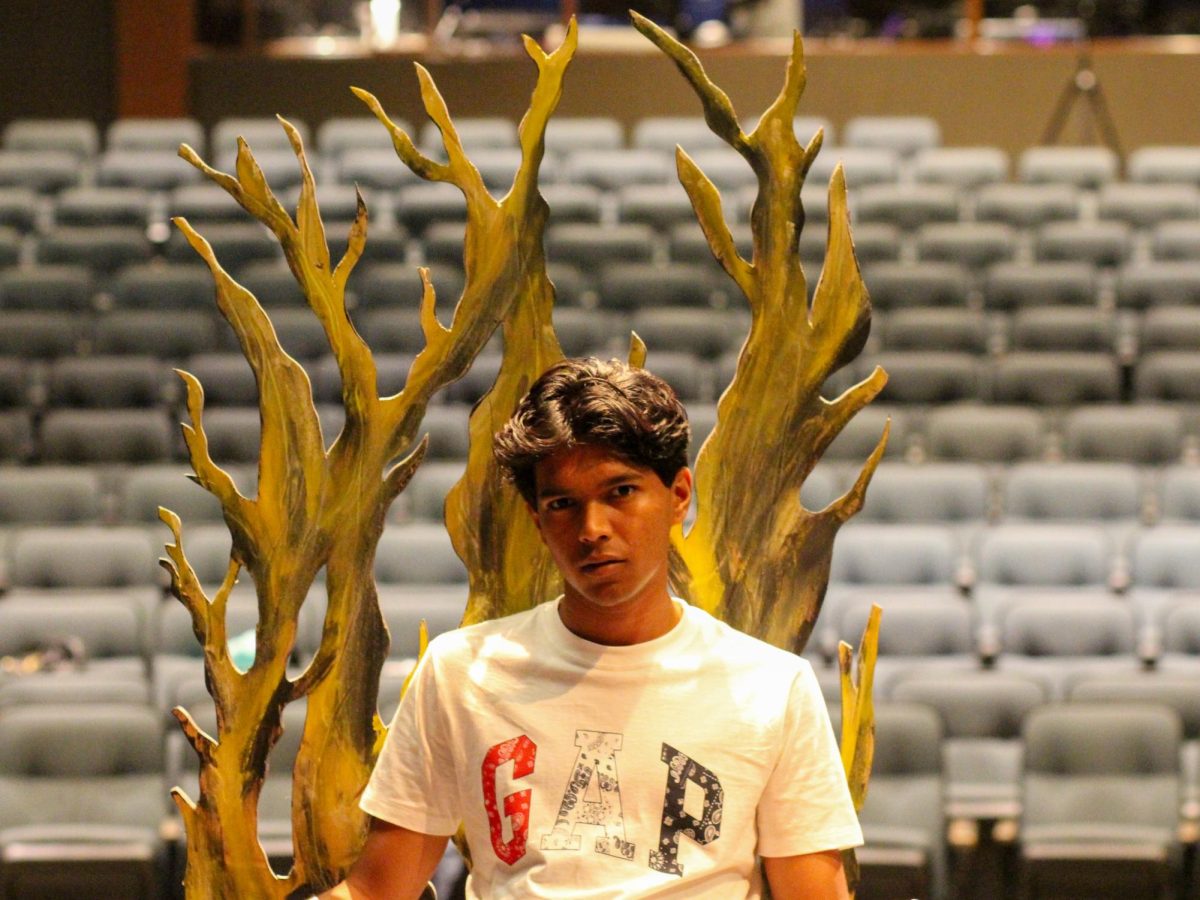

In the junior Honors American Literature class, students are all assigned to read The Scarlet Letter, in which the main character, Hester Prynne, is publically shamed for adultery. Consequently, she has to wear the red letter A to display her ignominy to the Puritan society. In order to analyze the book and better understand Hester’s experience, the class donned their own unique letters to showcase their flaws.

As a writer, I typically enjoy discussions about emotionally charged and exceedingly personal topics, so I looked forward to examining my own and other’s greatest flaws during our Scarlet Letter unit. It seemed to be a chance to verbalize my internal scrutiny without feeling like that archetypal melodramatic person who inundates every conversation with harrowing life stories, which always seem to end with some didactic conclusion where the narrator has finally completed or is making great progress on turning their life around.

When it came time for us to bear our own scarlet letters and show our flaws with eight by eleven inch, symbolically decorated letters, I expected a certain recognition from those at least somewhat familiar with me—the “oh yeah, she has that flaw, it’s pretty noticeable now that I think about it” response, conveyed in a way that suggests approbation for being accurately introspective, proceeded by a short discussion about past manifestations of my shortcoming.

By the time I wore my letter on Monday, people were accustomed to the group of juniors wandering around school with their flaws clearly displayed. The few who asked about it were my friends, wondering what word I had chosen. But when I said that I was insecure, most of my friends and peers looked at me skeptically. It was as if Hester Prynne had embroidered an F for Fidelity—albeit, of course, garnering a much less severe reaction.

Going into this activity, I didn’t want to choose a flaw that would make it seem like I was trying to conceal my most blatant limitations, which include control and narrow-mindedness. These, I decided, are external results of a more internally true but less overt flaw. Because of my insecurity, I put up a false front, and I don’t give much of myself away. I tend to equate admitting other’s strengths with demonstrating my own inadequacy, which makes me stubborn. Consequently, I have unrealistic expectations in terms of what I should be able to accomplish, and when I don’t achieve those goals, I often give up instead of trying harder, because trying harder would mean admitting and facing my imperfections rather than pretending they don’t exist.

But when people typically think of insecurity, it comes with the image of someone who never speaks up in class and who hides behind a book to avoid being seen. Insecurity can present itself in such a manner, though like all flaws, the “symptoms” are different. During my conversations with friends and acquaintances, I was asked why I would choose that as my greatest flaw—I seem more than willing to express my opinions in class.

I probably grew more comfortable with my flaw at the end of the day, but in some ways I also wasn’t portraying my true flaw, at least not wholly. Hester Prynne may be an adulterer, like Emma Bovary and Henry Crawford, but equating the three sins would be a drastic oversimplification. “I’m insecure,” reveals about as much of me as “I’m human.” It is reassuring to know that everyone has flaws, but I realized—and even more importantly, internalized—how multifaceted all our characteristics our, and how inaccurate our perceptions of others can be.