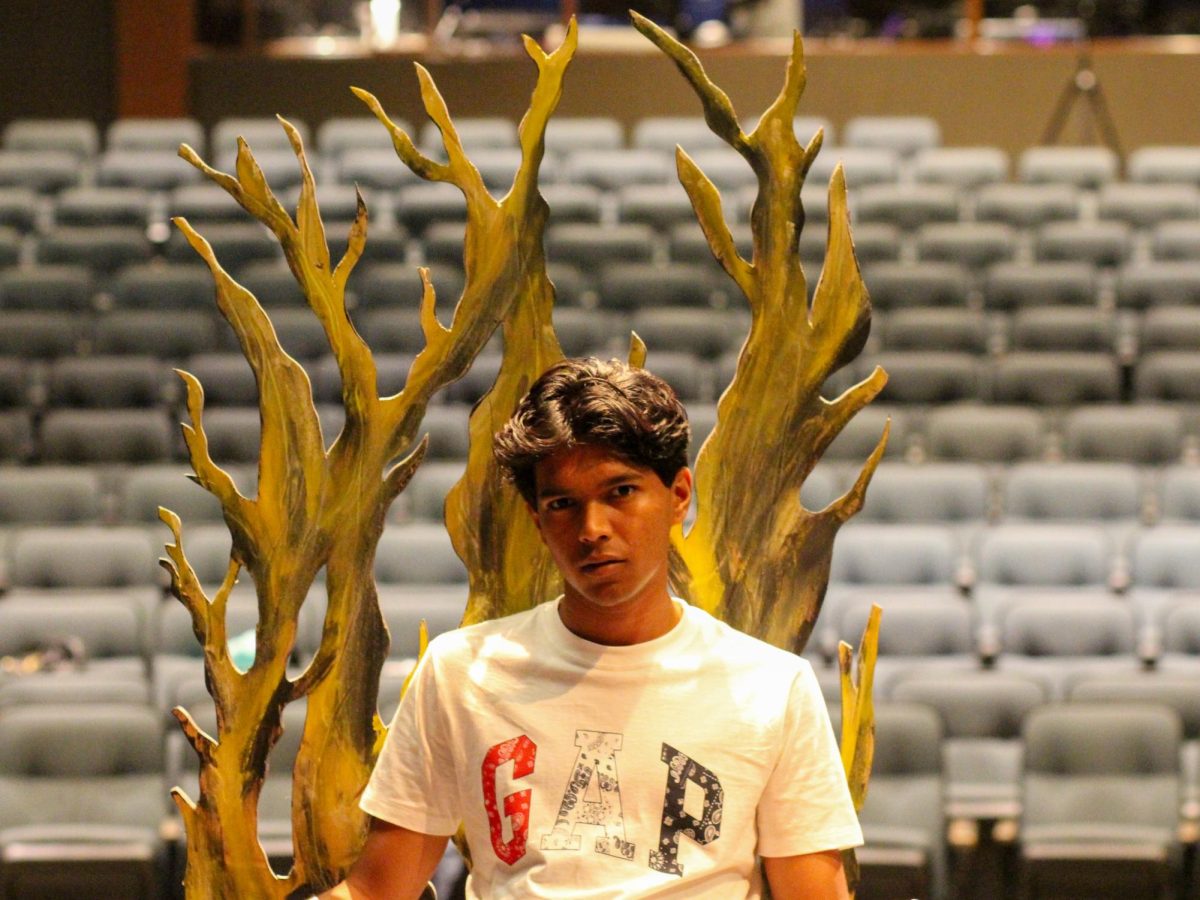

Dr. Andrew Patterson, an associate professor at Stanford University and the division chief of Critical Care Medicine in the Department of Anesthesia and Pain Medicine, came to Mountain View High School on Friday, December 5th, to discuss the recent outbreak of the Ebola virus in West Africa. His presentation strove to clarify facts from fiction on the virus as a result of recent hysteria and misinformation.

On March 31st, Patterson received a letter from the World Health Organization that said there was a need for volunteers to be deployed in West Africa to help treat an Ebola outbreak that had started in December of 2013. Patterson was contacted for his experience in “austere environments”, particularly in Africa where he had worked for a little more than ten years. He was unable to go to Africa due to prior commitments, but he kept in touch with Rob Fowler, the head of the World Health Organization efforts in West Africa and one of his trainees at Stanford during the 1990s. Fowler went on and visited different locations around Sierra Leone, Guinea, and Liberia where the disease was prominent. Over the summer, Patterson received email updates from Fowler and the messages appeared to be getting progressively worse as time passed.

“At one point, [Fowler] sent a note saying that when the clinics became overwhelmed with patients, they would be too full to care for new patients so these patients would simply lie down and die outside the doors of the clinic,” Patterson said.

Ebola in West Africa was centered around three countries: Sierra Leone, Guinea, and Liberia, but spread quickly outside of those regions. The first patient diagnosed with Ebola was a two year old kid in West Africa. While scientists do not know how exactly he contracted the virus, they are suspicious of fruit bats who can carry Ebola.

According to Patterson, the biggest issues with this outbreak is the number of healthcare worker deaths and the unprecedented spread of the virus. The lack of resources and personnel to aid in the treatment of disease also contributed to its endemic spread.

Patterson believes that in the past, minimal transportation helped contain small outbreaks of the disease in Africa. When he was working in Rwanda, most of the individuals had never even been in a car before. However, the modern advancement of technology and accessibility of transportation may have played a role in carrying the disease to more locations.

Another issue on containment appears with the unfavorable conditions of the environment.

“[Guinea] is about a 110 degrees- it’s humid- and it’s so difficult for the patients who are already febrile and very sick,” Patterson said. “They can’t stand being in rooms so what they do is they take their blankets and sleep on the ground outside and you can imagine why that would be a problem in terms of containing the outbreak.”

Misconceptions of the Ebola virus come into play when people overestimate the ease in which an individual can contract the disease.

“It turns out Ebola is a wimpy virus, you can clean it with some clorox wipes and it dies. It’s not that easy to get [Ebola] in you,” Patterson said. “If you shake the hands of someone who has Ebola, you’re not going to get Ebola unless you have cracks in your skin or you take your hand and touch your face and it gets around your mouth, nose, or eyes.”

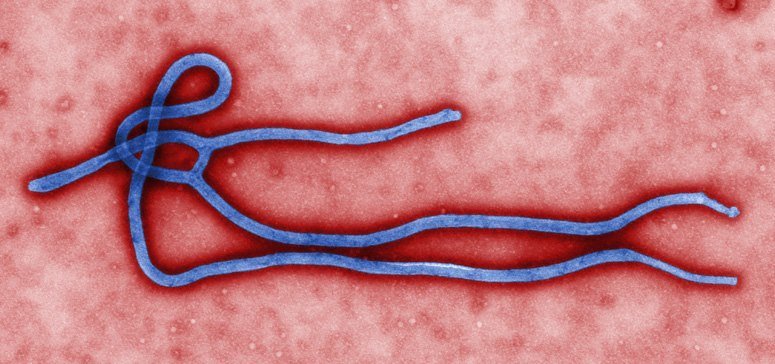

Ebola, a virus with only seven genes that can produce eight proteins, has infected already more than 10,000 people in West Africa- a number that Patterson believes is only going to increase exponentially with time.