From time to time, Stephen Widmark’s students salute him. As it turns out, there is no greeting more suitable for the former US Air Force pilot turned science teacher.

Widmark, an AP Physics 1 and C teacher, was an F-111 Weapons system officer in the US Air Force from 1982 to 1988. After graduating from UC Berkeley with a degree in physics, Widmark said that he was burned-out from academia and thought that flying in the Air Force would be “exotic.”

He was stationed in England, and he was deployed to Spain, Italy, Turkey, and Germany. During one of his missions, Widmark was flying supersonic over the Mediterranean, 200 feet above sea level. They were 200 miles from the southern tip of Italy when they ran out of gas and had to chase sheep off the runway to land in Crotone, Italy.

However, Widmark said that his experience in the military was not as exciting and challenging as he expected. He was moved to an eight-hour desk job at a wing headquarters, the command center for a specific wing in the Air Force, in England. Eventually, he said that he left the military because he was burnt-out and wanted to protect his political ideology.

“I came from a pretty liberal background,” Widmark said. “And, politically, the military tends to be conservative. It kind of disturbed me a little bit when I saw a lot of the old timers, the people that had been in [the Air Force] for 20 years, and their worldview seemed to me to be very skewed.”

During his early teaching career in the 90s, Widmark developed a flight-simulator physics curriculum based on a fictional aircraft called the A20A Vindicator using his experience in the Air Force.

“I certainly learned a lot,” Widmark said. “I think [the military] is a good place for a young man to be.”

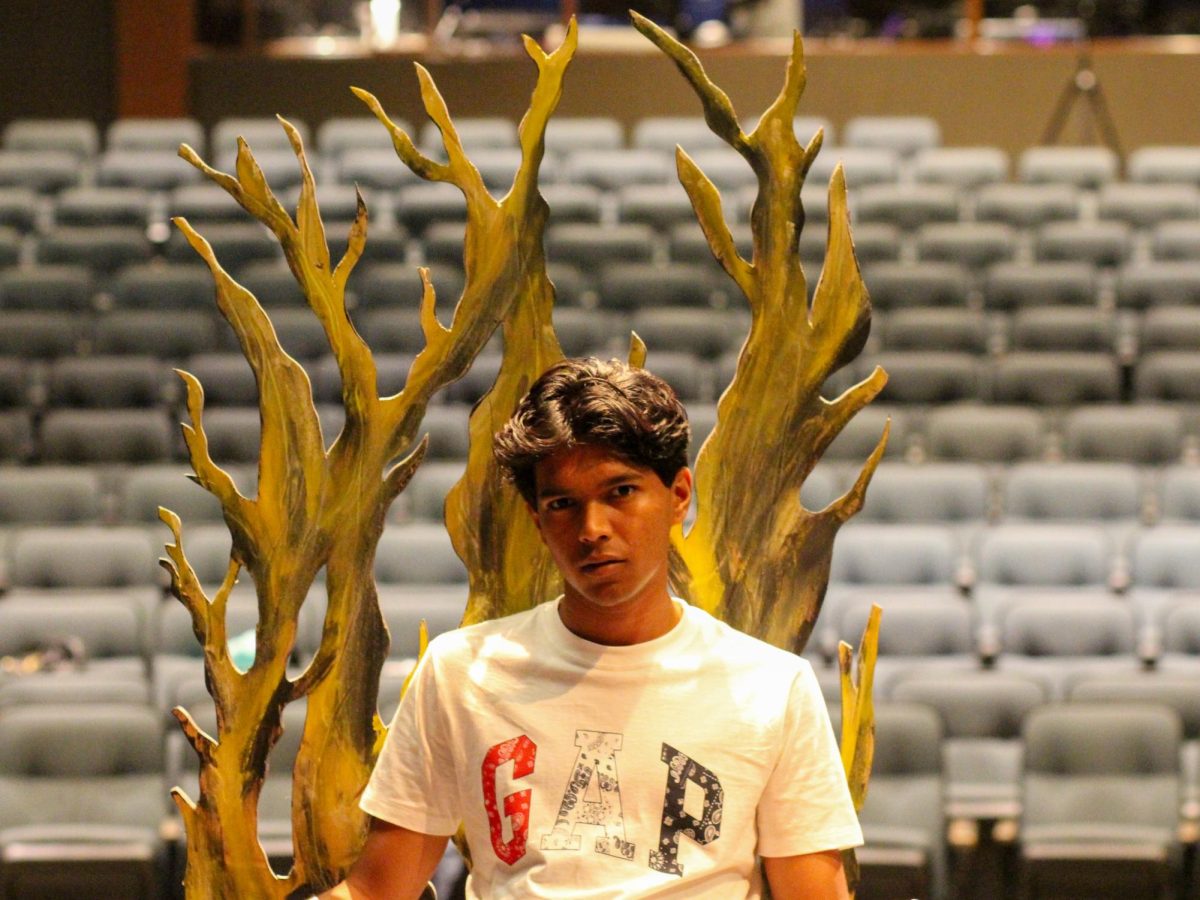

History and social science teacher David Ortiz was an 11B Infantryman in the US Army from 2010 to 2014. He said that joining the military was equivalent to joining a brotherhood, something that he did not have growing up without siblings.

“There’s a certain bond that happens when you go through such trauma together,” Ortiz said. “There’s an intimacy.”

Ortiz was stationed in Kentucky and deployed to Afghanistan for eight months.

“Deploying was a kind of a surreal experience,” Ortiz said. “Especially for a first timer because you’re going into a war zone and you don’t know if you’re going to come back.”

However, Ortiz said that going to Afghanistan made him develop a stronger sense of appreciation.

“The village we were next to had kids running around barefoot,” Ortiz said. “I really saw that they were happy with what they had. Here, we are not happy until we have the newest iPhone. These people have nowhere near what we have, yet they are happier than we are.”

Ortiz said that he was discharged for an injury that left him unemployed and homeless for six months. His military friends housed him for some time and he moved around to St. Louis,Chicago, Las Vegas, and Bakersfield, California. He eventually settled in San Diego.

“It almost feels like society completely rejected you,” Ortiz said of his discharge. “I sacrificed a few years of my life. I lost some friends, but I can’t get a job. You feel like you’re basically at square one again.”

Ortiz said that he was drawn to teaching because it was “military-like” in structure and leadership. He said his “unit” is now his students, not fellow soldiers.

“There is a mission that we undertake in [the classroom],” Ortiz said. “You are going on a journey together for nine straight months. There are connections and bonds that last forever because you endure the trauma of the class.”

Engineering teacher Dr. Curtis Smith was an intelligence officer in the Navy from 1988 to 1995 and a reservist until 2011.. Smith said that with a single mother who could not afford college tuition, joining the military was one of his few options. Joining the military was “an opportunity for adventure” — a change from growing up in the 10,000 person town of Canton, Connecticut.

“I do have a romanticism for the ocean and the sea,” Smith said. During his seven years on active duty, Smith was stationed in San Diego, and he was deployed to Iraq, the Persian Gulf, and several countries in the Pacific.

He said it was the “moments of stupidity” with his fleet that kept him going. He said the fleet broke a monotonous 111 days at sea by catapulting a Chevrolet Impala off of the aircraft carrier.

In August of 1990, Smith was deployed in the North Indian Sea, heading for Australia on an aircraft carrier. He said that his captain ordered the fleet to turn around back to the Persian Gulf. Saddam Hussein, former dictator of Iraq, had ordered an invasion of Kuwait.

“I remembered feeling that ‘shit, this is real,’” Smith said. “‘These are real bullets and real missiles. Training is over.’”

Smith said that one of the more difficult parts of joining the military was giving up freedom.

“[I] grew up in America where we have unlimited freedom [and] unlimited rights,” Smith said. “We speak our mind [and] we do what we want. [When] you join the military, you give that up. An order is an order. It’s not a request. It’s not open to your interpretation or your opinion.”

Ortiz shares this sentiment.

“You can’t call in sick,” Ortiz said. “You can’t miss a day. You can’t go to 7-11 and grab an ice cream. You can’t do a lot of things we take for granted. One of the first things [me and my fellow soldiers] did when we came back was hit up a Baskin Robbins because we hadn’t had ice cream for so long.”

According to Smith, although it took time to grow into the military, it was more difficult to transition back into civilian life after being dispatched for a diving injury.

“I was used to being called sir,” Smith said. “I was used to being saluted. There was a time when I flew more in helicopters than I drove my own pickup truck.”

After leaving the military, Smith joined Troops to Teachers, a military program that paid veterans to get their teaching credentials to teach at low-income schools for four years. Smith said that he is able to use his military experience to teach the practical applications of engineering. He also said that he tends to take himself less seriously than other staff.

“I’ve been shot at, I’ve been stabbed, I’ve been in combat zones, I’ve jumped out of airplanes,” Smith said. “Nothing we do in education is life or death. I don’t get as hung up or stressed out about things as most people.”

Wellness coordinator Michelle Burgos was a 25U Signal Operations Specialist in the US Army Reserve for six years after high school. As the middle daughter of two immigrants, she said that she felt like an outcast for most of her life. Joining the military was her chance to give back to America.

“This country gave my parents so much,” Burgos said. “They gave them papers. My dad bought his first home. I felt like I wanted to do my part.”

However, according to Burgos, her parents were against it — joining the military was an act of defiance.

“I always felt weak being a woman of color,” Burgos said. “I had seen a lot of stuff in my life that always put the woman as a victim. There was a lot of trauma in my life that made me want to join the military and be strong and be able to protect myself when I needed to.”

Burgos completed basic training in Georgia, Advanced Individual Training in South Carolina, and was stationed at Moffett Federal Airfield in Mountain View, California. Burgos said that completing basic training was her most difficult experience.

“Their whole purpose is to break you, both physically and mentally,” Burgos said. “So they trash talk you. They make you do these insane physical workouts. There was a little bit of sexism and also racism in the military. There were girls that would cry every day trying to go home.”

When Burgos graduated basic training, she said that it was the first time that her mom said that she was proud of her. According to Burgos, now, her experience in the military is the first thing her parents talk about.

“People [who] don’t know what it’s like in the military or what [soldiers] go through might judge [the military],” Burgos said. “When it comes to wars, they might not quite understand that we’re all mostly just soldiers following orders. After I joined, I realized it’s a big honor to be part of the military.”

After returning from the military, Burgos said that she struggled with panic attacks and anxiety.

“[The military] made me push down more of my feelings,” Burgos said. “Because you want to be so strong, there is no time to process everything that is going on with you emotionally. So you start to bottle it up.”

However, Burgos said that working with students at MVHS has helped her mental health.

“My job makes me happier,” Burgos said. “I love being around kids because they’re hilarious. They are so young, and they are dreamers. It makes us, older people, remember that we were once like that.”