This article was originally published in a print edition of the Oracle in February 2024.

On June 29 last year, the Supreme Court of the United States ruled that race-conscious college admissions were unconstitutional under the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment. This ruling has drastically changed admissions processes for colleges around the country, many of which used race-conscious admissions policies such as affirmative action.

The ruling, which has made policies like affirmative action illegal at higher education institutions across the nation, came at a time when there had been increased scrutiny of college admissions practices from critics and supporters.

According to Oxford Languages, affirmative action is defined as the practice of favoring individuals belonging to groups labeled disadvantaged. This practice has come into the spotlight recently, as investigations into Harvard University’s and the University of North Carolina’s affirmative action programs were released last summer.

“[They] argued that any consideration of race was unconstitutional,” said Lisa Stulberg, an Associate Professor of Sociology at New York University.

Stulberg herself said she has always been in favor of affirmative action and said she believes that taking it out of the “toolkit” of colleges and universities may significantly reduce racial diversity on higher education campuses.

“[Affirmative action] is an important tool, both for opening the door for a wider range of students and for creating a classroom environment and a campus environment that is more diverse,” Stulberg said.

However, many students don’t feel the same way. Sophomore Sophia Zhang said that although she understands affirmative action can aid schools in combating systemic oppression, she feels it affects her, as a person of Asian descent, and students of similar racial backgrounds in a negative way.

Race-conscious college admissions policies have been under increased scrutiny due to controversies over exclusion and unfairness to certain races. As a result, experts like Stulberg say that this could lead to investigations into other “controversial” admissions practices, such as legacy admissions.

According to the New York Times, legacy is a boost given during the admissions process to children or grandchildren of alumni, making them more likely to gain admission; many critics of this policy claim that it exacerbates socioeconomic inequities.

2023 MVHS graduate Natalie Mark said she strongly believes colleges should abolish their legacy policies because they give an unfair advantage to already economically and racially privileged students and families.

While Stulberg and others said that intentionally inclusive policies such as race-conscious admissions are a step in the right direction, they agree that these policies are only a “band-aid” solution for long-existing inequities within college admissions.

“In order for everybody to be equal, you have to have equity,” said David Ortiz, a history and Ethnic Studies teacher.

Legal Implications

Examining the legal implications of legacy admissions within the context of affirmative action reveals a complex interplay between fairness, equal protection, and constitutional considerations.

Throughout history, there have been a multitude of SCOTUS cases that have restricted the use of affirmative action. The 1978 Regents of California v. The Bakke ruling allowed the use of applicants’ gender, race, etc as a factor in admission. SCOTUS upheld race-conscious review again in its 2003 Grutter v. Bollinger decision, which allowed race to be considered to attain diversity. However, state-wide restrictions have also been imposed, such as the 1996 Hopwood v. Texas ruling banning race-based considerations for admissions at the state level.

Affirmative action, at the University of California, Los Angeles, for example, contributed to a more representative demographic before 1996. Due to this, the Latinx population among accepted applicants significantly increased, showcasing that systemic changes beyond affirmative action alone can empower historically marginalized groups in higher education, Spanish and Ambassadors teacher Lauren Camarillo said.

“In California, the population of Latinx people is 39 percent,” Camarillo said. “However, in many private universities in California, that percentage is much lower.”

In 1996, voters in California passed Proposition 209, prohibiting the consideration of race, sex, or ethnicity in public education, including admissions to public universities. As a result of passing this legislation, enrollment rates of Black and Latinx students dropped significantly, said Michael Treviño, the former Director of Admissions of the University of California System.

“The numbers really plummeted for African Americans that had been at [the University of California, Berkeley and UCLA],” Treviño said.

Treviño said that Black students had made up around 7 to 8% of undergraduate students at UC Berkeley and UCLA. After Proposition 209 passed, those numbers dropped by about half, and affected Latinx students even more dramatically.

More recently, in 2023, with the Harvard v. Students for Fair Admission case, SCOTUS ruled that affirmative action was unconstitutional. Following this ruling, selective colleges nationally have had to re-evaluate their admissions practices for the 2023-2024 admissions cycle.

“Colleges have [added] additional questions to their application, supplemental questions that ask about your experiences,” Treviño said. “The [SCOTUS] decision allowed institutions to still consider students’ experiences and so it became very important for colleges who did not ask those kinds of questions before to ask those questions.”

Treviño said it is also important to acknowledge that this decision affects a very small portion of colleges in the country. Most colleges in the United States are not highly selective, meaning that the decision will not impact them as they do to the Ivy Leagues of the college system.

As colleges navigate between permissible race considerations and legal restrictions, the threat of legal challenges persists, Stulberg said. Balancing priorities around diversity, fairness, alumni preferences, and potential lawsuits remains a constant challenge for universities. While limited affirmative action models have SCOTUS approval, barriers to practical implementation persist.

“It’s looking at an expanded world of [Proposition 209] applied everywhere,” Treviño said. “Not just the public [colleges] in California, but public and private universities throughout the country that are selective.”

What Opponents Say

Affirmative action and race-conscious college admissions were first instituted to try and remedy decades of racism and systemic inequalities that put certain demographics, like Black and Latinx Americans, behind others. However, many believe that affirmative action as a policy can discriminate against other racial demographics, like Asian and white Americans.

Though she said she agrees with the basic concept of affirmative action and its goals, in terms of uplifting marginalized communities, Mark believes that the system is currently flawed, and needs revision.

“I believe affirmative action has been weaponized to pit people of color against one another,” Mark said. “Many East Asian communities feel that affirmative action works against them, as argued in Harvard vs. Students for Fair Admissions.”

Stulberg said that one of the main criticisms of the policy, which has been part of recent lawsuits, is that any consideration of race in admission is racist. Lawyers who created cases against Harvard and UNC for example, believe that affirmative action lowers the standards for underrepresented students of color, and is therefore unfair to white and Asian students.

“They say that taking race into account in any way is unconstitutional under the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment,” Stulberg said. “They’re using the tools of civil rights.”

Zhang said that while she thinks such policies do give more people of specific backgrounds more opportunities, it comes at a disadvantage for others.

“It’s not one person’s fault that they were born to a specific race,” Zhang said. “It shouldn’t be used against them.”

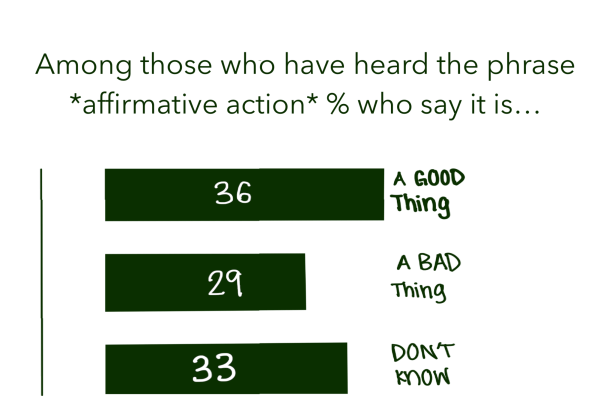

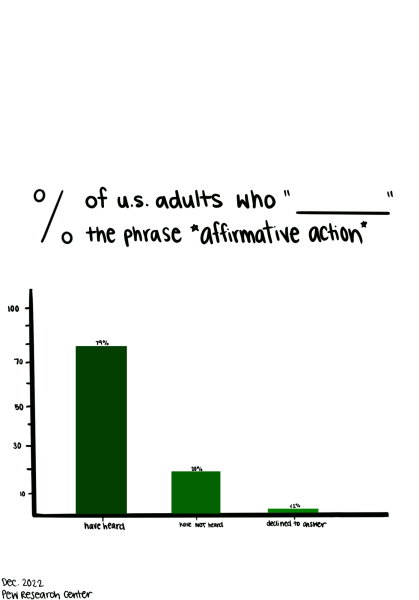

In a 2023 survey done by the Pew Research Center, half of Americans said that they disapproved of selective colleges considering race and ethnicity in admissions. In the same survey, 49% of Americans said they believed considering race or ethnicity as a factor made admissions less fair.

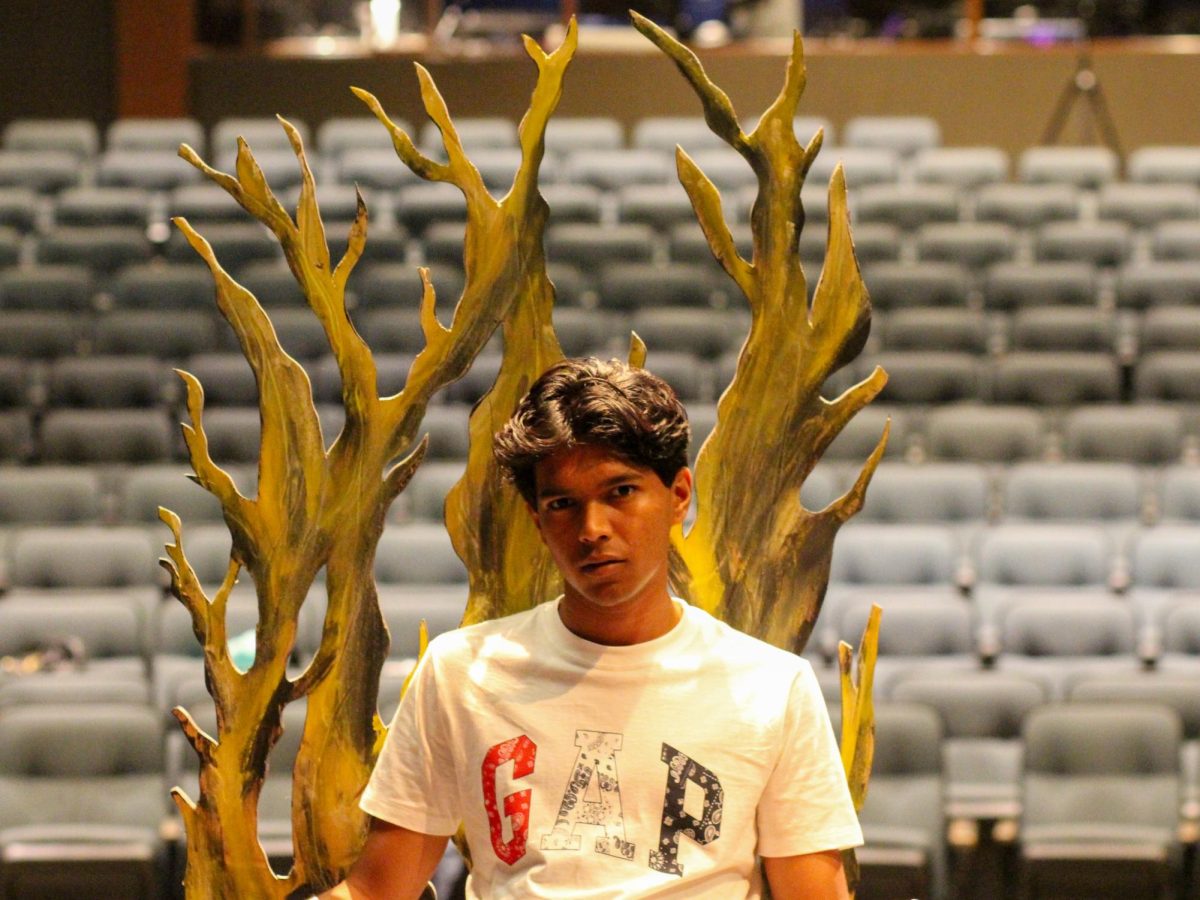

Junior Hrishikesh Lakshman said that he believes college admissions should solely be based on merit and skill. The intent of race-conscious policies are fine, he said, but the application of them can be detrimental.

“You’re hurting other people by denying them the chance when they deserve it, they worked hard,” Lakshman said. “They want to go somewhere and then they’re denied based on the affirmative policy. It’s like you’re trying to help other people but you’re still hurting people in the process.”

Ortiz said that he is in favor of affirmative action policies, as long as students demonstrate that they are up to the standards of the respective schools. The standard is the standard, he said, and schools cannot drop it for some students.

However, he said that if students of color or students from underrepresented backgrounds can prove that they have done enough, or met the standard for that selective school, it is even more impressive.

“A person of color automatically has less, they’re already at a deficiency when they’re born,” Ortiz said. “But [if] they are able to prove that [they achieved] the same standard as this other person who went to an amazing school … this person has demonstrated that they are that much more worthy.”

In terms of legacy admissions, Ortiz said that such policies allow generational privilege to continue without individuals having to prove their merit. According to Forbes, almost 50% of private universities consider legacy status in admissions, and that rate can increase to over 80% at more selective schools with lower acceptance rates.

“It’s just one of those things where you have it or you don’t,” Vaezeasfshar said. “It’s not fair in nature. There’s no merit-based [component] to it.”

Both Zhang and junior Evan Shiu believe that legacy admissions are completely unfair and provide unfair advantages to certain applicants. People don’t put as much effort into applications and preparing for admissions because they know legacy may be able to get them in, Shiu said.

“Who your parents are aren’t necessarily who you are,” Zhang said. “It just makes no sense that a college would put more consideration into a person just because their parents fit the values of the [school].”

What Proponents Say

MVHS senior Adam Faradjev said that colleges have many incentives to maintain relationships with their alumni — and their family members — in order to perpetuate their prestige.

“Through legacy admissions, they’re keeping the brand of their school, and that’s how they maintain their status or prestige,” Faradjev said.

Faradjev said that while legacy admissions provide preferential treatment towards individuals with higher socioeconomic statuses, the question to consider is whether or not that poses a problem.

Faradjev said that colleges only use legacy for a small number of students, so it is still possible to still achieve diversity without removing legacy admissions. For example, according to the Dean of Admissions at Brown University, only around 10% of admitted students on average are legacy students, which

“I don’t think legacy admissions alone can perpetuate a lack of diversity because even at Stanford [which has] legacy admissions, I still see a very, very diverse class of individuals similar to that of Mountain View,” said 2023 MVHS graduate Barbod Vaezeafshar, who is currently attending Stanford.

Vaezeafshar said the student body at Stanford is very diverse in terms of background despite what people may think. Students come from different socioeconomic backgrounds and are not all from the “top of the social hierarchy.”

“I think legacy admissions only perpetuate a lack of diversity when there’s also a lack of other measures to actually improve diversity at that school,” Vaezeafshar said.

Before the SCOTUS decision, many higher education institutions used affirmative action to improve diversity at their schools. MVHS senior and first generation incoming college student Adeleny Farias said it helps give equity to those who are not supported by the system.

“It’s this idea of equality versus equity,” Farias said. “Affirmative action is that way of giving equity to students who, for example, don’t have legacy or are low income and first generation families.”

Faradjev said the ruling on affirmative action in higher education institutions only prevents race from being used as a determining factor in admissions but applicants can still tell stories related to their race in their essays.

“I think by reading those stories, the admissions officers still get a sense for who the applicant is and they can still achieve diversity within their class,” Faradjev said.

He said applicants can not only showcase their backgrounds through their essays, but through other supplemental activities like extracurricular involvement related to their culture.

“Your background is a big part of who you are [in] your application,” Faradjev said.

Addressing Root Inequities

Some proponents of affirmative action say that the goal of the policy is to bring more racial diversity into the classroom, stemming back to the 1960s where colleges started to be part of the racial progress movement, Stulberg said.

“The government has a compelling interest in having diverse classrooms and having diverse professions,” Stulberg said.

However, both Ortiz and Stulberg say that the policy itself doesn’t do much, if anything, to address historical inequalities and disadvantages inherently present in the lives of people of color.

“Affirmative action, to me, is just a bandaid,” Ortiz said. “You’re trying to control the fire instead of preventing the fire. The fire is already out of control.”

In order to truly address such issues, like educational inequity and the growing wealth gap, the solutions need to start from the foundation, Ortiz said.

“You can try to finagle tests, you can change requirements,” Ortiz said. “But you’re not dealing with the base foundation issue. Where is the fire starting?”

Ortiz said that this “fire,” starts at a local level with K-12 education. Across the country, schools are on drastically different levels in terms of education quality and resources available.

“How do you expect something equal to come out of that?” Ortiz said.

Although race-conscious college admissions do play a role in placing a temporary ‘bandaid’ on these historical inequalities, the gap that exists between demographics is far too big to be solved through a single policy itself, Stulberg said.

“It’s kind of like running a race and being [chained down] the first 250 years, while the other person is just running around and around,” Ortiz said. “The misconception is that because you’re free now, you can do whatever you want. But the person who’s been running around that track for 250 years, has 250 years worth of being ahead.”

According to the Census Bureau, in 2021, only 28% of the Black population, from ages 25 up, had completed four years of education. Similarly, only around 20% of the Hispanic 25+ population had attained the same level of education compared to 61% of Asian Americans.

To even think about race-conscious admissions as effective or ineffective comes from a place of opportunity, senior Radhika Kamran said.

“Saying [affirmative action] is going to be the thing that makes it equal or equitable, to have it or not to have it, is an incredibly privileged perspective to take,” Kamran said. “In fact, it’s quite miniscule in the grand scheme of things.”

Farias said she feels like the university system was built for predominantly rich families and white men. Although affirmative action intends to give more opportunities to marginalized students, solely giving everybody the opportunity to apply to college isn’t enough, she said.

“You need to give more support to the people that have [less] resources, those who live in areas where the education is not as strong,” Farias said. “We have to give them more resources.”

Many schools still require a submission of standardized test scores such as the SAT or the ACT. According to the Hechinger Report, even though more colleges are moving toward test-optional practices, colleges are still taking these scores into account.

Students of privilege and higher socioeconomic status have the option of using test prep tutors, classes, and programs to maximize their SAT and ACT scores. Farias said that she and her AVID classmates didn’t even know what the SAT was until sophomore year, while others were already taking prep classes as freshmen.

“If your main concerns are safety, having a job, caring for your family, if there are other responsibilities in your life and you don’t have the money for something like test prep … you don’t have the advantage,” Camarillo said. “If you have fewer resources, it does not set you up for success. Higher resources are a reflection of success on tests.”

Paraphrasing American abolitionist and orator Frederick Douglass, Ortiz said that it’s harder to reconstruct grown adults, compared to children. It’s difficult to break down ideologies that were instilled in individuals’ minds as children. Yet, going back to foundational inequities, and offering solutions and ideas for those, can make a world of difference, he said.

“Great teaching, great schools, great everything radically changes everything,” Ortiz said. “Affirmative action is minor. … You don’t solve any problems.”

2023 MVHS graduate Michelle Liou said that affirmative action is not effective in targeting historial inequalities because it doesn’t target the root causes of educational inequality and resource inaccessibility before higher education.

Policies like legacy-based admission, especially, do not do anything to increase diversity and can exacerbate the already existent lack of equity between demographics, Ortiz said.

Legacy admissions are essentially a continuation of an implicit power structure, allowing demographics that were always ahead of the rest to stay at the top, without proving their merit, Ortiz said.

“[Legacy] is like the opposite of affirmative action,” he said. “It reinforces privilege instead. The problem with legacy is that a person can underperform and that gap can be filled in just by their family times. That’s not right.”

Ortiz said that if he had children, he wouldn’t want them to get a “free walk” into the school just because of their father’s alma maters— they would have to self-demonstrate that they’re qualified and deserving.

Stulberg said that she believes that legacy admissions are a form of privilege, and a way to reproduce that privilege over generations. No matter how one thinks about it, there is class privilege to legacy, she said.

Ortiz said he was never part of that privileged class, but earned his way into his educational privilege, escaping homelessness and childhood hardship. However, for “one-percenters,” legacy admissions are a way to perpetuate class inequality, he said.

“It’s an implicit barrier again because the admissions for college are finite,” Ortiz said. “That legacy kid takes a spot that doesn’t go to somebody that’s actually deserving of it.”

However, the real root of the issue, according to Mark, Stulberg, Liou, and others, is the education system and the inequities that it can perpetuate due to lack of resources or low-income students, among many others.

“I wish we as educators and people, all people that care about education, would really look at preventing the fire, [rather] than putting it out,” Ortiz said.