Students speak out about sexual assault

Feb 8, 2021

Trigger warning: graphic descriptions of sexual assault

Hannah* said that in the eighth grade, she was sexually assaulted multiple times by her then “boyfriend,” a junior at LAHS. She said he would lock her in his house or car and refuse to drive her home until she would give in, and as she couldn’t drive, she felt trapped.

“He would hold me down on the bed, and actually like lay on top of me and rape me. At that point, I didn’t really know what sex was, it wasn’t something that I had been openly talked to about so I didn’t understand quite how wrong this was. I could tell by the fact that it made my soul and my body hurt that it wasn’t good,” Hannah said.

Student experiences

She said she was emotionally and physically manipulated and abused, and the sexual assault began with kissing and oral sex and escalated into penetrative sex within months.

“I’d always say like, ‘I don’t want to, just take me home, I don’t want to do this.’ And he’d be like ‘no no after after’ and so after saying ‘I don’t want to’ once or twice, I kind of just gave up saying no,” Hannah said.

Despite wanting “to sit in a hot shower and scrub all [her] skin off” after these experiences, Hannah said she didn’t register his actions as assault.

“I didn’t have anything to compare it to. I thought that I needed to do this for him to appreciate me. He’s driving me around so I have to repay him in this way,” Hannah said.

She said she didn’t tell anyone what was happening in the moment because she blamed herself for getting sexually assaulted and thought others would too.

“I thought very strongly for a long time that it was my fault because I had gotten into a “relationship” with him at such a young age. I just thought that people would tell me it was my fault for doing that, tell me that I should have told people when it was happening,” Hannah said. “It didn’t really cross my mind that if I told someone, that they would help.”

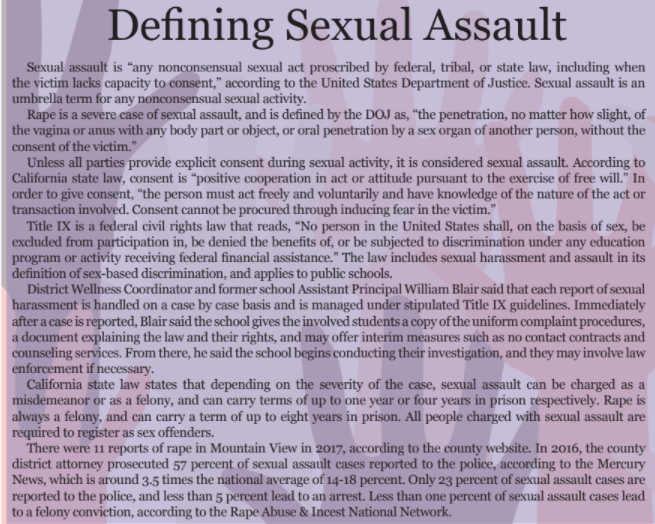

Teenage sexual assault victims often do not report their perpetrators for two main reasons: they are uncertain that the incident is worth reporting, and they develop an avoidance response coined “adaptive indifference,” which “allows teens to do nothing, thereby remaining loyal to their friends, dating partners, schoolmates and peer groups,” according to Dr. Karen Weiss, who has extensively researched sexual victimization and wrote “‘You Just Don’t Report That Kind of Stuff’: Investigating Teens’ Ambivalence Toward Peer-Perpetrated, Unwanted Sexual Incidents.” Furthermore, 60.4 percent of women on average do not recognize their experience as rape even though it fits the definition, according to Wilson and Miller, who wrote “Meta-Analysis of the Prevalence of Unacknowledged Rape.”

Hannah said while she had initially suppressed the memories of assault, months after she ended the “relationship,” she regained emotional confidence and the memories began to resurface. She needed someone to talk to, so she told her sister, who then helped her tell her parents.

Hannah said she decided to report her rapist for sexual assault around a year after the events unfolded. After telling her family, her mom called the sheriff’s department, and Hannah was pulled out of school one day and came home to a detective and four police officers in her living room. She said they asked her questions and she made an official statement.

“I told them everything. They knew how to ask the right questions, because at first I was kind of hesitant opening up,” Hannah said. “They made sure that I knew that none of it was my fault.”

Hannah said that a couple days after making her statement, the detective asked her to “cold call” her rapist in order to get an apology or acknowledgement of his actions, which would be admissions of guilt.

“I had to call him, pretend that I was alone, and talk to him. I did get him to say that he hurt me, I didn’t get him to say the word rape,” Hannah said.

“I kind of just gave up on saying no”

After that, Hannah said he was arrested and spent a night in jail before being released on bail. He later had a court appearance that Hannah said she did not attend. She said that while she knew of four other girls that had been sexually assaulted by him, she was the only person who made an official statement.

“They were thanking me for doing it and saying ‘I don’t personally have the ability to come forward but I want to say thank you for what you did.’ That once again broke my heart that these girls felt like they would be treated badly for coming forward, or that their parents would be mad at them for coming forward,” Hannah said. “I was surrounded by people who were supporting me through it but I know a lot of people that it happened to that were not.”

However, the District Attorney said there was not enough hard evidence to convict, and did not push the case all the way through, according to Hannah. She said she was initially “heartbroken,” but it still gave her the closure she needed and the ability to heal.

She said that despite only telling her closest friends, many people found out about her assault because the arrest was public. While the majority of responses were positive and supportive, she said a couple of his friends threatened her and accused her of lying for attention.

Though her rapist had already graduated from high school, Hannah said she told the administration about her situation. She said former assistant principal, now district Wellness Coordinator, William Blair, pulled her out of class one day, asked her how administration could best support her, and gave her suggestions on how they could help. Hannah said she was grateful for the suggestions and took them.

A picture of Hannah’s rapist was given to all of the campus security guards, and Blair talked to all of her teachers along with Hannah to let them know what she was going through. She was also given a parking spot next to a security camera so that if anything happened near her car, it would be recorded.

“It made me feel safe, and it made me feel heard, and it made me feel respected,” Hannah said. “They did a really good job of continuously checking up on me and making sure that I was still doing okay, even months afterward.”

Isabella* said that when she came to the doctor with flu-like symptoms in eighth grade, the doctor sexually assaulted her by penetrating her vagina with his hands under the pretense of “checking [her] vaginal glands.”

Similar to Hannah, Isabella said it took years before she felt comfortable telling others. She said she only told her mom over the past summer because looking at people wearing surgical masks due to COVID-19 triggered memories of her assault.

Isabella’s therapist filed a sexual assault report on her behalf around three years after the assault occurred. Within a couple of days, Isabella said she talked to a “super understanding” police officer about her experience.

Isabella said that she had to go in person to the Department of Family and Children’s Services to make her official statement explaining exactly what happened to her. Because she reported her assault during the pandemic, she said she was interviewed alone, without a parent or a sexual assault advocate, which made her feel extremely uncomfortable.

“I thought that I needed to do this for him to appreciate me”

“I remember getting very cramped up and I felt very unsafe. [The officer] was just super intruding and not friendly at all, and just seemed to doubt me. I was sobbing, I could barely talk,” Isabella said.

She said that even during the interview, she still partially blamed herself for the assault, and “felt bad” for her doctor and the consequences that she believed he would face.

A month after her interview, Isabella said that the investigator on the case called her mom and told her that the doctor that raped her was “very nice and very understanding” and no further action was being taken. Isabella said that Child Protective Services told her mom that this was the second time someone had reported this doctor.

“They’re supposed to interview his other patients to make sure it never happened to anyone else. If they actually interviewed them after his first offense, they would have found out about me, but they didn’t, so they obviously were not actually researching the patients thoroughly,” Isabella said.

False Accusations

Alumnus Ryan* said he was falsely accused of sexual assault two years ago. His ex-girlfriend reported the assault to her teachers, who were then required by Title IX policy to report the incident of alleged prohibited conduct. He said his parents soon after received an email from his teachers explaining the allegation of sexual assault against him.

Ryan said he then spent a couple afternoons talking to Margarita Navarro, who was the Title IX coordinator at the time, about the allegations against him, the potential consequence of getting kicked out of Middle College, and the sexual nature of his relationship. The Title IX coordinator is the district authority responsible for handling all reports regarding Title IX policy, which prohibits sex-based discrimination in public schools, including sexual assault and harassment. The current coordinator is Leyla Benson.

“I explained to them how it was from my perspective. I was trying to get cuddles, I was trying to get close to her, and she would say no and it made sense to me that maybe she would feel better like ten minutes later, and I’d say ‘hey can we cuddle again.’ I suppose that was kind of stupid, but it wasn’t sexual harassment,” Ryan said.

He was later interviewed by a detective and made an official statement, where he explained his perspective once more. He said the detective told him that if someone said no, he should leave them alone instead of repeatedly asking, and he said he understood.

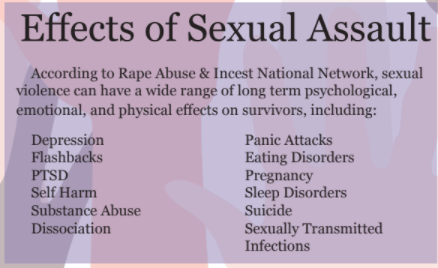

After making his statement and waiting for more information, Ryan said he was terrified of being falsely accused and planned to commit suicide if he was charged with sexual assault.

After a couple weeks, Ryan said he was informed that they found no evidence of wrongdoing. He said he was not allowed to talk to the alleged victim or talk about the case with his friends, and therefore did not know what she said or why specifically the case was dropped.

Sex Education

Junior Michelle Kelman said she felt her sophomore year health class lacked an emphasis on sexual assault and rape.

“Unfortunately, I think [rape culture] is one of those things that is scary, and a very uncomfortable topic. I think a lot of people drown out that noise and they don’t want to hear about it and they don’t want to accept it. And I don’t think that should be why we don’t teach it,” Kelman said.

In order to get the most out of sex-ed, health teacher Tami Kittle said she thinks it should be taught in-person during freshman year. Currently, around 25 percent of the student body opts out of in-person health and takes the class online through the MVLA Adult School, according to health teacher and department coordinator Heather Boyle. The program does not cover sexual abuse or rape, and only started covering consent this year after a switch from the online platform Odysseyware to a new online platform, Edgenuity.

Hannah said that her lack of sex education made it extremely difficult for her to understand what was happening to her, which hindered her ability to seek help when she was going through a physically and emotionally abusive relationship.

“The sooner we start talking to kids about it, and the sooner we open up a line of conversation, a lot of the shame will be gone, a lot of the guilt will be gone, and I think it’ll be a lot easier to have conversations. If I’d known what [rape] was, I would have told my parents that this was happening to me,” Hannah said.

Boyle said that she thinks the health curriculum should also highlight how pornography can give unsafe perceptions of what sex should be to “young and impressionable” students.

“The reality is that the most of the porn that is free is the most likely to not show consent and to not show healthy, caring relationships,” Boyle said.

Teenage boys exposed to violent pornography were 2–3 times more likely to report perpetrating threatening sexual violence, and girls exposed to violent pornography were over 1.5 times more likely to perpetrate threatening sexual violence compared to their non-exposed counterparts, according to a study conducted by Dr. Whitney Rostad and others, published in an article titled “The Association Between Exposure to Violent Pornography and Teen Dating Violence in Grade 10 High School Students.”

“If you know people aren’t supporting what you’re saying, it’s very easy to feel silenced”

Kittle said she has implemented a new sex-ed curriculum this year called Teen Talk that covers topics including what constitutes a healthy relationship, consent, and sexual violence protection.

To teach the curriculum, Kittle said she implements interactive activities, where students act out scenarios and engage in discussions. Her students responded to surveys saying that they felt comfortable during class, according to Kittle.

“They realized that I’m not this straight edge teacher. I give them [the curriculum], but I also go into more depth. If they have questions that they think are embarrassing, they realized that it’s not embarrassing to ask because it’s a question that probably everybody else has,” Kittle said.

Party Culture

When senior Sophie Bellisario was at a kickback, a small party, during the summer before her sophomore year, she was sitting on her male friend’s lap and he put his hands into her pants while she was drunk. Bellisario said she was embarrassed to say no while it was happening because the people she was with were her coworkers, and older than her.

“I think to them, they’re just like, ‘well you know they didn’t say no’ and he couldn’t see my face so he just didn’t think it was a big deal, didn’t think much of it,” Bellisario said.

This left Bellisario feeling “disgusting” and “powerless” over her own body, but she said the worst part was that the other people at the kickback criticized her for what had happened.

“My coworkers would be like ‘That was crusty, why’d you do that? Why did you let that happen?’ Whereas he got nothing, no one gave him shit for it, he felt no remorse, he was fine,” Bellisario said.

Bellisario said incidents like this are common, and she has frequently seen boys grope girls at parties. She said it often goes unnoticed because there are many people in one room talking while music is playing, so it is “easier to get away with.” Senior Christina Olson also said she has gotten groped at least twice at every concert she has been to.

Olson said she feels frustrated as she believes many sexual assault situations have been “glossed over.” She said that even if other people hear about these acts being committed, there is often little to no social consequence. She said she has seen situations where the assailant is able to maintain their popularity even if many people know they committed sexual assault.

“The victims don’t speak up, or at least not to adults or to authority, because they know nothing’s gonna come of it. It just brings up all this PTSD for no actual beneficial outcome,” Bellisario said.

Bellisario said she thinks many men believe that consent is when someone does not say no rather than an enthusiastic yes. She said she believes that they typically do not think they are assaulting someone.

Olson said that victims often get blamed for their own assault because of rumors. She said when she hears people victim blaming, she tries to counter their arguments by giving them basic examples of sexual assault and showing them how the victim has suffered as a result of coming forward.

“I find myself having to jump into conversations with basic, simple statements such as a person who is in a committed relationship, a marriage even, can still be raped by their partner. To me that seems like very elementary information about what really constitutes rape and rape culture in general,” Olson said.

She said that she believes the reason why so many boys support alleged perpetrators of sexual assault is because “they see themselves in the position of the boy and think ‘oh my god that would ruin my life if I ever accidentally came on to a girl too hard.’”

Olson said many students often fail to understand that one reported sexual assault is a symptom of a pattern of behavior, rather than an isolated mistake. Turning a blind eye to the reported crime and blaming the victim only furthers this culture of sexual assault.

Bellisario also said that victim blaming is prevalent because not many people speak out against it.

“I don’t think there’s enough people doing it, especially because it’s just a hard subject and if you know people aren’t supporting what you’re saying, it’s very easy to feel silenced,” Bellisario said.

Olson said this culture of staying quiet about assault and actively trying to discredit the victim about their experiences only furthers this culture of commonplace and normalized sexual assault and harassment. While this is prevalent at parties and in many high schools in the Bay Area, she said it is less severe at Mountain View, attributing the decreased severity to the increased willingness of students and administration to hold perpetrators publicly accountable for their actions.

“The way that you stop making that an accepted behavior is by confrontation”

“The way that you stop making that an accepted behavior is by confrontation. Brushing it off is just the worst thing you can do with a situation as grievious as a rape culture because it only will worsen. It will not get better if it’s not attacked,” Olson said.

It is also common for victims to blame themselves for what happened, according to Bellisario. She said that victims often convince themselves that it was their fault because they did not say no. Bellisario and Olson both said that it is also common for victims to only realize that it was wrong after it happened.

Bellisario and Olson both said they know many people who believe that consent is fully possible under the influence of drugs and alcohol, and said that consent under the influence is a complicated issue. Bellisario said she has had positive sexual experiences under the influence where she believes herself and her partner both consented. Olson said she believes that consent can still be possible if someone is not heavily intoxicated.

Even though many women have experienced sexual assault and harrassment at parties, Bellisario said that it has not deterred people from going to parties, even when they know alleged assailants will be there.

Olson said she and her friends stay careful while going to parties and have avoided certain parties because she knew men with “creepy tendencies” would be there. She also noted that when one of their friends is heavily intoxicated, another one of their friends stays with them to watch out for them.

“I just try to be a good ally out there to people who have been through stuff because I know what it’s like to go through stuff myself. Our only job as humans is really to look out for each other, so that’s all we can really do,” Olson said.

*Indicates that the students name has been changed to maintain their anonymity due to the sensitive nature of the subject