Amidst pandemic-induced economic and health challenges, families living in oversized vehicles are now prohibited from parking along the streets of Mountain View, which may displace residents.

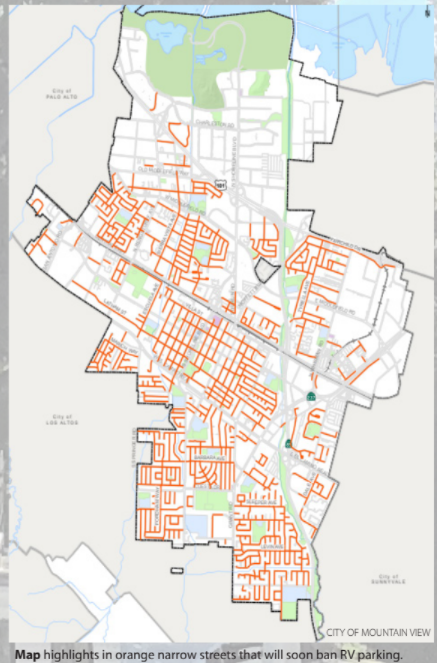

On December 8th, the Mountain View City Council unanimously voted to reinstate its RV parking ban on most city streets, following the passage of Measure C this past November. Measure C passed with 56% of the vote and prohibits the parking of oversized vehicles, including recreational vehicles, on narrow streets 40 feet or less in width, which accounts for around 75% of the city’s streets.

Enforcement requires 2,600 signs to be installed, which will cost close to one million dollars. Though activists advocated for a delay at the City Council meeting due to the pandemic, the council voted to continue with its plans. Mayor Abe Koga estimated that the first signs will be put up around April.

To accommodate RVs that will have to move, there are currently five safe parking lots that can hold a total of 67 Oversized Vehicles, while there are about 325 oversized vehicles in MV, according to Abe Koga.

In addition, Project Homekey, a modular transitional housing project that will convert motel rooms into temporary housing, is projected to serve around 150 people at a time and help around 300 people in a year, according to Abe Koga. She said that Project Homekey is projected to open in February.

“If you do the math, with Project Homekey and the safe parking lots, I’d say that in less than two years, we should be able to help every homeless person in Mountain View that wants to be helped,” Abe Koga said.

She estimated that there are around 600 homeless MV residents. However, this is based on a survey conducted in 2019, before the pandemic began, and the very nature of homelessness makes it difficult to accurately count.

“This is not about kicking people out of Mountain View, we are actually finding places for people to go,” Abe Koga said. “I don’t think living in a vehicle is a permanent housing solution.”

“What am I going to do? This is my home city”

Abe Koga said the city has put almost $6 million toward homeless services over the past two to three years, and is currently working on creating several permanent affordable housing projects. She said the city currently has almost 2500 units of below market rate housing.

However, former Mayor Lenny Seigel said that this housing is largely inaccessible because it is already filled up.

“Most of these places don’t even have a waiting list,” Seigel said.

He said the lack of available affordable housing results in homeless residents relying on the Community Services Agency to find them affordable housing, which is mostly outside of the city. Seigel said Measure C would only exacerbate this displacement of residents, which is especially dangerous amidst the pandemic.

“I believe that most of the proponents of Measure C in the narrow streets arguments are people who just don’t want to see poor people living in vehicles on the streets of Mountain View. It’s part of a gentrification goal to make Mountain View seem more like Los Altos or a wealthier city,” Seigel said.

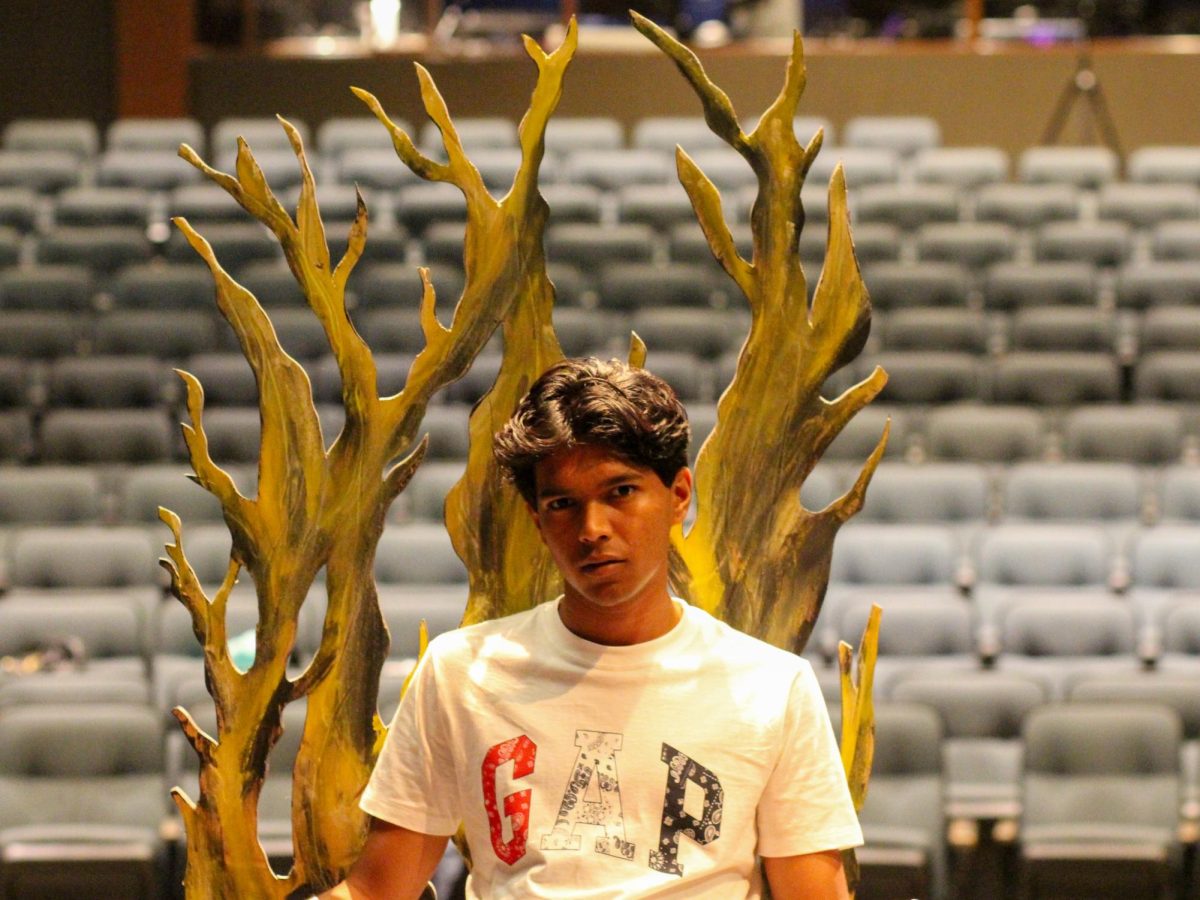

Rouel Fernandez, who is retired and lives in a motorhome parked in a safe parking lot, said he is nervous and stressed about getting displaced. He said he chose to live in a motorhome because he frequently travels across the country to visit national parks and family for months at a time.

“There is nowhere to park a motorhome in the city of Mountain View, unless you do the safe parking, which is temporary. One day, it’s going to go away. And when it does, what am I going to do?” Fernandez said. “This is my home city and I’m a citizen of Mountain View. That to me is the biggest stress I have.”

Furthermore, Seigel said the safe parking lots are not accessible to all, as there are too few spots available, and requirements that many families cannot meet. One such requirement is that the family should have access to the RV’s keys. Many families are renting their RVs for shelter, and therefore do not have keys to drive them.

Such vehicles are parked on MV streets, which ban overnight parking and require the RV to move every 72 hours, which is difficult for working families, especially when they do not have access to their keys. Seigel also said many families are afraid their parking spot will be taken if they leave.

Fernandez said he has received around 22 tickets over the past two to three years before he moved into the safe parking lot, which he said was “not too bad” compared to other families.

Seigel said he does not believe the outreach to vehicle residents should be primarily led by the police.

“Many vehicle residents reported to me that the police were using [the 72 hour rule] as a basis of harassing people. It was hard to prove that they’ve actually moved the vehicle,” Seigel said. He said the police stopped enforcing the 72 hour rule when the pandemic began.

Abe Koga said that she supports Measure C because the RVs parked on narrow streets create traffic safety issues and are a public health hazard.

“There’s certain streets where they’re just lined up from one end to the other,” Abe Koga said. “You really can’t see if there’s cars coming down, and so it was sort of like a leap of faith driving down these streets, hoping nobody was there.”

Seigel said there are other ways to solve this issue.

“When I was mayor, I met with the CEO of Palo Alto Medical Foundation who showed me how oversized vehicles were encroaching on the driveway and people couldn’t see. I called it to the attention of the Public Works Department, and they painted the curb red maybe 25 feet on both sides of the driveway and put up signs saying no tall vehicles for another 25 or 50 feet,” Seigel said. “When there’s a problem like that, you can solve it without just throwing people out.”

Abe Koga also said that human waste from the RVs is sometimes dumped onto the streets and storm drains, creating a public health hazard.

“Because of the [public health] hazards that were being created, it became an issue and we started hearing from our community that we needed to do something about it,” Abe Koga said.

Seigel said that he wants to slow down the process to make sure that the residents have another place to go and are not displaced out of their home city. He said many of the 25% of streets that are not categorized as narrow already have signs prohibiting parking. This means that in practice, much more than 75% of the streets would prohibit RVs. He said he is advocating for more safe parking lots and the opening up of the remaining 25% of streets for oversized vehicles to ensure these families have a place to go.

Additionally, Seigel said there is going to be a lawsuit to try to reverse Measure C, which will be filed once the city moves forward with the ban. He said there will be several housing insecure residents that are plaintiffs.

However, Abe Koga said that many other cities have similar parking bans. She said that MV has the second largest safe parking lot program in the Bay Area, and that homelessness relief typically comes from the county level, not the city level.

“I just don’t understand why there’s so much criticism for a city that’s doing way more than anybody else,” Abe Koga said.

Abe Koga said that her goal is to transition residents living in oversized vehicles into permanent housing.

“The streets that are not covered by Measure C should be opened up to people”

“The purpose is not to continue to have RVs,” Abe Koga said. “The whole point is to try to get folks transitioned into permanent housing. Even the safe parking lots, we should be able to close them over time because the folks that need help should be getting help.”

However, Seigel said the number of homeless residents in MV is severely underestimated, and Measure C will result in severe displacement because the city is not creating enough space for the residents to go.

“Safe parking is a great solution, but there’s just not enough of it,” Seigel said. He added that many residents would rather stay in their vehicles than move into temporary housing, because they know they will have their vehicles in the future, whereas the housing is temporary.

The underlying problem

“The homelessness crisis has been building for decades and there are a lot of contributing factors,” said Bruce Ices, CEO of LifeMoves, a program that provides long-term shelter and case management to homeless people looking to re-enter into stable housing.

The lack of affordable housing is one of the main reasons the Bay Area’s homeless population is the third largest in the U.S, according to a study conducted by the Bay Area Council Economic Institute. Ives said that while housing costs have consistently been rising, low-income wages have not.

“As the price of housing has gone up, wages for low income earners have not kept pace, so people simply can’t afford to pay the rent,” Ives said. “That’s the largest dynamic that’s driving the problem.”

Mountain View is no exception to these trends. The County of Santa Clara conducts a survey every two years and as of 2019, there are 9,706 homeless people in the county, a 31% increase from 2017. The City of Mountain View’s homeless population has risen 46% since 2017. In the MVLA District alone, 734 students qualify for Free or Reduced Lunch according to the California Department of Education. This number is slated to increase during the pandemic.

The local expansion of tech companies, such as Google, are exacerbating the housing crisis, according to Alba Garza, Foster Youth Coordinator and McKinney Vento Liaison.

“It’s the driving force behind the high rents,” Garza said. “It’s impacting their housing options.”

According to a study by Think Tank Working Partnership USA, “The additional housing demand created by Google’s planned downtown San Jose expansion would exacerbate the local housing crisis and raise local rents by hundreds of dollars per family annually.”

Rouel Fernandez said many of the people he has been neighbors with in safe parking lots are there because they were priced out of their homes and couldn’t afford to continue paying rent.

“The cost of living in Mountain View is out of control,” Fernandez said.

Also contributing to the housing crisis is a lack of sufficient mental health and addiction resources. Ives said that one in five of the “singles” that his company provides shelter for are veterans, who have not been able to access resources for their mental health issues.

According to Garza, undocumented immigrants are also susceptable to homelessness because they can’t lease or rent apartments without the necessary documentation.

“I just don’t understand why there’s so much criticism for a city that’s doing way more than anybody else”

A culmination of these issues means individuals and families are forced to find or create shelters and provide for themselves amidst a deadly pandemic.

“We often think of [homelessness] as someone who’s living in a tarp, or behind a bush, or pushing a cart, but it’s very different in Mountain View. Yes, of course, they are a percentage of the population but it is not the majority. It’s a very unique situation in our area,” said Malia Pires, Executive Director of the Reach Potential Movement, that has pivoted to providing food, shelter, social services, and other necessities of life for the economically disadvantaged during COVID.

One growing population are the vehicularly housed, people living out of their cars or in Recreational Vehicles (RVs) or trailers. According to Pires, people living out of RVs and cars face a slew of struggles, including a lack of access to electricity and running water.

While Ives’ organization LifeMoves aspires to find the homeless community more permanent housing by providing resources and stable housing for months at a time, he said most overnight shelters are only a temporary fix.

“There are some shelters that run on a model where people line up every night, you get a bed for the night. It’s called “three hots and a cot”: three hot meals and a bed and that’s about it,” Ives said. “That model can be helpful in getting people to shelter, especially in cold or wet weather, but it’s not really effective in moving people back to stable housing and breaking the cycle of homelessness.”

Pires said it is also common for several families to share small apartments.

“On the other side of homelessness are families that live with two, three, four, or five families in one apartment,” Pires said. “It’s extremely common that you might only have access to the living room and restroom, but no kitchen access or something along those lines.”

This living situation creates an environment where COVID is likely to spread, according to Dr. Dana Romalis, who, prior to working at Stanford as a primary care physician, worked with the Santa Clara Valley Medical Center on their interdisciplinary Valley Homeless Healthcare Program for 10 years and continues to work with them one day a week.

“With COVID, if one person is out for the day, gets in a car with several people, does construction, and comes home, they could infect the whole household,” Dr. Romalis said.

COVID-19 has exacerbated the housing crisis in other ways, threatening many community members with eviction.

The state signed into law the Tenant Relief Act that imposes a temporary moratorium between March 1, 2020 and January 31, 2021 on evictions of qualifying residential tenants for failure to pay rent because of financial distress related to COVID-19.

“You’re always in fight or flight mode”

“That’s a protection for families that are low on rent, so what happens when that protection is removed?” Pires said.

Once the eviction moratorium expires, “we’ll see another wave of economic hardship and recession, and more families will face eviction or will fall into homelessness,” according to Ives.

“San Mateo and Santa Clara County have both been leaders in the fight against homelessness,” Ives said. “They’ve been strong partners in figuring out the urgent needs of the unsheltered community.”

Healthcare

These urgent needs include physical and mental healthcare and accessing basic needs such as electricity, bathrooms, and food.

Dr. Romalis believes that mental health is the biggest issue facing the homeless community, as being homeless often exacerbates or even causes mental health issues.

“Whether they had mental health problems and ended up homeless or ended up homeless and now have mental health problems….once you get into that cycle of poverty and homelessness, it’s really hard,” Dr. Romalis said.

Chronic stress is another result Dr. Romalis has observed of homelessness.

“There’s a lot of stress associated with the instability of housing,” Dr. Romalis said. “It is a lot of work to be homeless because to get fed, and to get your resources for the day…maybe to find and get to a shelter… takes a lot of effort and stress.”

English Language Development teacher and instructional assistant Leslie King said this effort is shared among homeless youth, affecting their mental health in the same way.

“As a young person [in these situations] you have adult concerns, because you have a responsibility,” King said. “Many of us are lucky enough not to have had [the same concerns] as young people, but for those who do, it makes what was already hard, much, much harder.”

Lack of resources

A student living in an RV spent her nights doing her homework by candlelight because she lacked electricity, according to Assistant Principal Daniella Quinones.

“The thought of someone doing their homework at candlelight is just so mind boggling for some of us that have never experienced that in our lifetime,” Quinones said. “We can’t imagine that that would ever happen in our community, yet it does.”

For people living in RVs, the lack of electricity makes cooking, having a refrigerator, and heating nearly impossible, according to Garza. Many RVs also do not have running water.

“There’s this overwhelming anxiety that you live with. You’re always on fight or flight mode. There’s never a moment where you’re just at peace because you don’t have your basic needs being met,” Garza said.

Fernandez said in addition to the lack of electricity and running water, many motorhomes are very old and have many issues, including cardboard covering broken windows and parts of the vehicle, and broken propane systems.

“Out of 28, or so [motorhomes in the safe parking lot,] probably 20 to 22 of these the motor homes are very very old, because they were bought really cheap, because that’s all they could afford. A lot of things don’t work,” Fernandez said.

To provide for students without electricity, the district has distributed solar power generators, chromebook laptops, and mobile hotspots according to Bob Fishtrom, the District Information Technology Director.

Fishtrom said that even before the shift to distance learning, most classes and assignments required technology, and the lack of access was detrimental to students’ learning. He said around eight percent of students in the district, or 325 to 350 students, were in need of a mobile hotspot, according to a survey the district sent out at the beginning of the pandemic. As of Dec. 1, 287 mobile hotspots were checked out..

“We understand that a mobile hotspot while it’s good, it’s not great, and it’s going to be limited in terms of speed and connectivity,” Fishtrom said. “Especially when you get into an environment like Zoom, where that takes up a lot of the computer processor and bandwidth, that can really drain down the connectivity stream [making it unreliable].”

Fishtrom added that he would like to work more closely with Google, given their proximity to the school and their internet service called Google-Fi.

“We want to do our part to ensure that [a widened technological gap] doesn’t happen but if challenges aren’t being communicated to us, we are kind of working blindly,” Fishtrom said. “So the big thing is to really have students and families advocate for themselves and contact [their] school site so we can do what we need to do.”

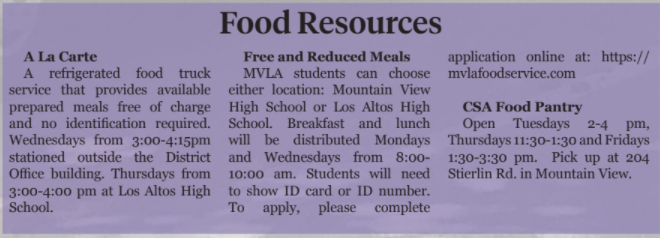

Another consequence of the pandemic is the lack of accessibility to food, according to Student Services Coordinator Huang Vo.

“A lot of students rely on the school serving lunch and breakfast, but if they’re not in school, they don’t get a meal,” Vo said.

One of the district’s food services is the A La Carte Food Truck, which takes food businesses would have otherwise thrown out and turns it into meals that families can pick up at the school, said Vo.

While the services have continued through COVID-19, food distribution has been moved closer to the communities in need to increase accessibility.

Fernandez said CSA and church-affiliated organizations drop off food resources directly to his safe parking lot several times a week, and almost all the families take advantage of the resource, because they often are unable to travel to receive the resources they need.

“Food banks often only operate on weekdays, and when people are working…they can’t take off work and get to a food bank and wait in line to receive provision,” Pires said.

Another helpful food resource are gift cards to healthier fast food restaurants like Chipotle, because many families do not have the means to cook their own food, according to Garza.

Quinones said that during the Spring, the district organized a food gift card drive for families struggling during the pandemic and was able to raise 50,000 dollars.

“They fill buckets of water and bring it back to their RV”

Pires said that COVID has also shut down many of the outlets that homeless people use to obtain basic necessities to live. For example, the unhoused often shower and use the bathroom in gyms using memberships, but since gyms as well as restaurant bathrooms and other facilities have been closed, they are left without a place to bathe or use the restroom.

“How do they go to the bathroom? Basically the only thing open really was a grocery store, if they could get to it,” Pires said.

Families now rely on public faucets and fountains in order to take care of their basic needs, according to Garza.

“They fill buckets of water and bring it back to their RV. Families that have electricity warm up the buckets, and that’s the way they take quick showers,” Garza said. “It’s a challenge, even to meet this very basic need.”

Garza said families take advantage of a program that offers showering facilities through CSA a couple times a month and travel to have access to friends’ houses and their facilities.

Even though Vo said the district is trying to do as much as they can to help, these are primarily temporary resources.

“Homelessness isn’t an issue that just goes away. Even with the added resources during the pandemic a lot of our families are struggling. It is real, and we need to do more,” Vo said.

Balancing with school

With the federal No Child Left Behind Act passed in 2001, the McKinney-Vento program was established to provide protections for unstably housed students such as those in foster care, sharing apartments with multiple families, and living in RVs or homeless shelters, according to Garza.

Garza said the McKinney-Vento Act will protect students who get pushed out of MV due to Measure C.

Garza said she works directly with students in the program to help them through managing their outside stressors with schoolwork, including the struggle to make enough money to live. Many of these students work one or more jobs while going to school, according to Garza.

“They’re trying their best to make their jobs work with their education,” Garza said. “So teachers are being very flexible when submitting assignments, and they are accommodating as needed, because we know the situation is so dire for [homeless students] when it comes to working.”

She said most of the McKinney Vento students chose Option A this semester, and are the first students with the option to join the school cohorts.

“They told me that they feel very exhausted and very tired. For example, they do their Zoom classes, and it’s over by 3:30, and after 3:30 they have to go to work from 4 to 9:30 or 10pm. At the end of the day, they don’t really have that extra desire or energy to complete anything outside of just the bare requirements,” Garza said.

Despite work taking up a large portion of their day, the situation worsens when work is unavailable.

“With the pandemic, a lot of things are closed. A year ago, people had jobs, and restaurants were up and going and even if you were a teenager it wasn’t very hard to find a job,” King said. “But now, it’s a challenge financially.”

But King said work is not the only reason homeless students must devote less time to school.

“If your situation is not stable, your first priority becomes just surviving,” King said. “You need to stay warm, you need to have a place to sleep, you need to have some stability in your life, so it makes it challenging to focus on school.”

Despite the difficulties of focusing on education, King said that when school was in person, it served as “such an important anchor for many of our students” as well as a place that provided “continuity [and] a community.”

“When you go through a hard time, it helps to have your community support. I think all of our students really miss that,” King said.