Student discourse mirrors a polarized election season

Nov 2, 2020

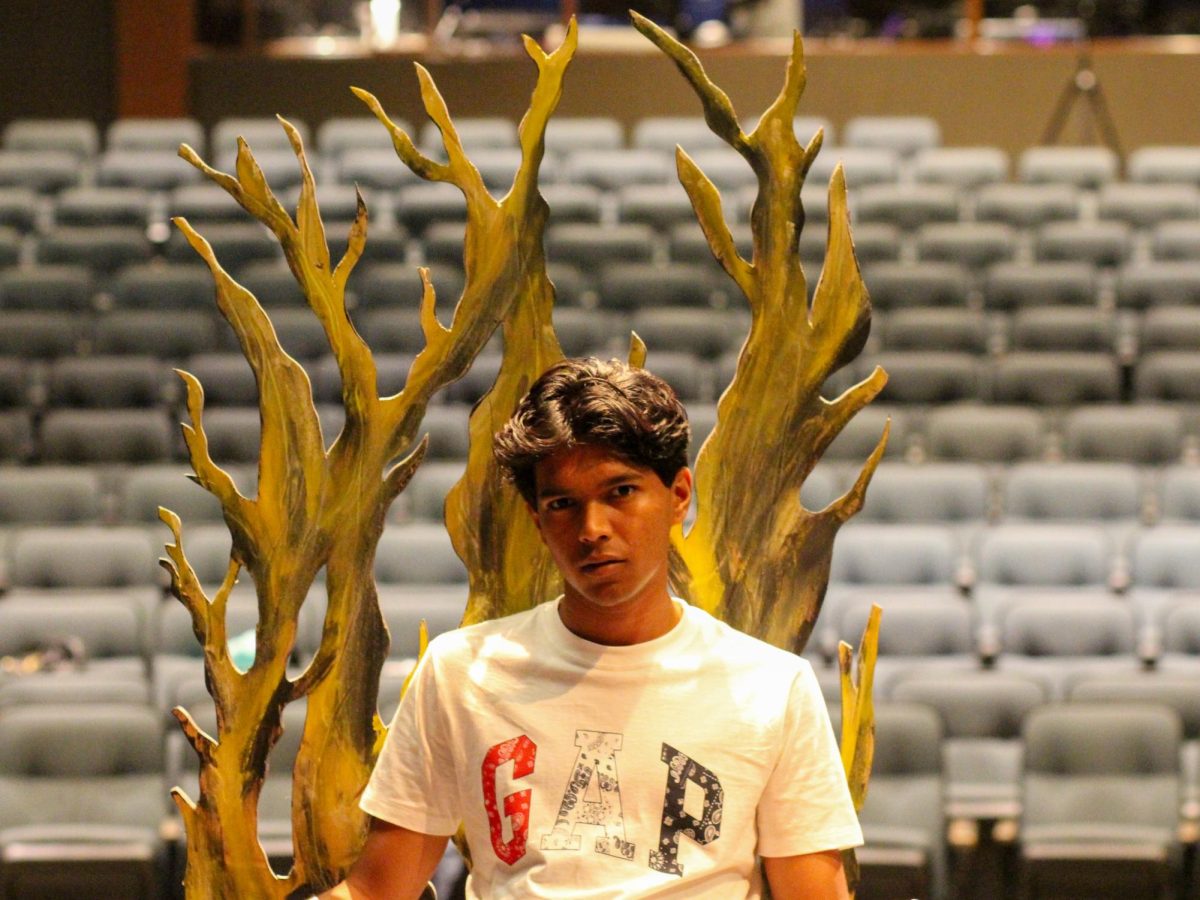

When junior Richard Zhang announced his support for President Trump on Instagram, he said he faced a slew of hate, mostly in the comments section of his posts.

Captioning his post “Today I will part ways with people for my beliefs… But I know today I am liberated. Today, I stop trying to fit in with the liberal agenda. Today, I stop pretending like I agree and start standing up for what I believe,” Zhang said he was labeled a racist and a traitor, and was met with comments such as “f*ck you.”

The post attracted over 100 comments in two days from conservative and liberal students alike, resulting in conversations and arguments about politics in America. With political polarization on the rise in the country, people on opposite ends of the spectrum try to reconcile their political differences, but more often, try to change minds.

A predominantly liberal population can create an “echo chamber,” where similar opinions and information get reinforced and opposing viewpoints often get shut down. Students tend to avoid conversations with people with opposing viewpoints, a phenomenon that has been furthered through social media, a more dominant platform for political discourse in light of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Student Discussion

Senior Roo Joshi, who identifies as liberal, said she cannot remember a single political conversation she has had with someone who she disagrees with, usually because she finds such conversations to be unproductive.

“It feels like a waste of my time,” Roo said.

Senior Yingen Poh, who identifies as conservative, said that when she speaks to people with opposing views, she often feels her views are not heard.

“I would explain myself and if they don’t listen or show that they’re trying to actually have a conversation, I know where it’s going to head,” Poh said. “It’s frustrating because I can’t get them to understand why [I think the way I do].”

Roo said she would only engage in a political discussion with someone on the other end of the spectrum if she “saw the potential to shift a perspective,” but according to Roo, that opportunity has never presented itself. As a result, she feels that there is an “ active avoidance” of political topics between right and left leaning students.

Political discourse among students has been described as mentally draining, exhausting, and dogmatic. This trend is representative of the country as 63% of liberal Democrats and 52% of conservative Republicans are likely to say they find political conversations with people they disagree with frustrating, according to the Pew Research Center.

When discourse does occur, it often happens between students with similar views and remains respectful.

Poh said she is not always looking to argue with someone about politics, which is why she mostly talks to people who already agree with her. According to Poh, she doesn’t speak to her liberal friends about politics at all.

“It feels like a waste of my time”

“I’m not looking to debate anyone, I just want someone to rant to or talk it out with,” Poh said.

Junior Evelyn Yaskin, who identifies as liberal, said that because of the school’s liberal leanings, most people she encounters agree with her.

“People don’t argue with me or try to change my opinion because most of the people I’m in contact with are accepting of [my stance],” Yaskin said.

Yaskin said she is used to hearing people who agree with her opinions, and it feels “odd” when she is exposed to the other side.

Roo and MVHS alumna Elise Joshi, who also identifies as liberal, said they would only engage in a political conversation if it doesn’t pertain to “human rights,” citing LGBTQ+ rights and the Black Lives Matter movement as examples.

“These things are a matter of human decency, so if someone wants to argue with me that gay people shouldn’t have the right to marry, I won’t be open to it,” Elise said. “But if you want to discuss rent control or something, I’d love to have a conversation and use facts and empathy to come to some agreement.”

Such exchanges of opinions and ideas predominantly occur online through social media platforms, especially in light of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Social Media

Zhang said he decided to publically share his support for President Trump after he got diagnosed with COVID-19. He said he asked other “closeted conservatives” for their opinions, all of whom thought it was a bad idea. He decided to post it anyway.

“The fact that people so close to me are so politically extreme as to wish death upon their political opponents… that was what made me really decide to stand up for what I think is right,” Zhang said.

Poh and Roo also said they primarily post their political opinions on social media platforms Instagram and Snapchat when frustrated.

“A lot of it was emotional,” Poh said. “You see a post and then you look at the comments and the comments just really piss you off so you’re like, ‘oh, I want to rant on social media about this, I’m going to post this and share my opinion, because I’m annoyed.’”

One example of this was when Poh reposted an Instagram post about a black woman doing “white face,” and wrote, “tbh let’s be fair white ppl get more sh*t on the internet than black ppl or pocs now,” among other comments. She said she was nicknamed the “racist white girl from Los Altos,” though Poh said she is not white, racist, nor a resident of Los Altos.

Both Zhang and Poh said that students tend to be less respectful online. Zhang said most of the “hateful” attacks after his post about Trump were in his public comments section, and people were more respectful when having one-on-one conversations with him.

“If the perception is ‘we’re polarized,’ are people reacting to that perception?”

Roo said this culture of constantly sharing and viewing opinions on social media was one of the reasons she decided to take a break from Instagram.

“I think that the Internet is a constant stream of opinions, and they can get really mangled. It’s really hard because you have access to anybody’s opinion whenever you want, and I don’t necessarily think that’s a good thing,” Roo said.

Roo said she sees two major consequences of this constant stream: blindly following others’ opinions instead of critically thinking for yourself, and getting confused about personal morals. She said these consequences made forming and understanding her own values and beliefs more difficult.

“If you’ve grown up with the Internet and you’re so used to reading people’s opinions and letting them affect you, it continues to do so no matter how old you are,” Roo said. “As somebody who’s just been way too influenced by it, I need to figure things out on my own.”

Middle College senior Tara Sabet also said political discourse, especially on social media, emphasizes “right” and “wrong” opinions.

“People are forgetting that political views are a spectrum,” Sabet said.

AP Government teacher Felitia Hancock also said social media contributes to the idea of “right versus wrong” opinions and the echo chamber effect because social media algorithms primarily show consumers the types of news and opinions they have looked at before.

“What people forget is Facebook, Twitter, Snapchat, Tik Tok… none of these companies exist to advance democracy. They exist to make money, and they’re going to design their products in order to maximize their profit. And they do it very, very, very well,” Hancock said.

Hancock said that she doesn’t believe political polarization is as prevalent as the media makes it out to be.

“I think polarization makes for good television… If the perception is ‘we’re polarized’, are people reacting to that perception?” Hancock said. “In the end, if they actually sat down and stripped away all the nonsense and just sat and talked, they’d find they have more in common than they realize. We’re not affording that space much anymore because it doesn’t go viral.”

Elise said while the inherent nature of social media easily allows people to reinforce their opinions and talk to like-minded individuals, she said she regularly tries to interact with people who disagree with her. Garnering over 46,000 followers on TikTok, a social media platform she uses to promote voting and show her support for presidential candidate Joe Biden, she said she regularly and actively interacts with people who disagree with her.

“If someone wants to argue with me that gay people shouldn’t have the right to marry, I won’t be open to it”

“I go live usually twice a week. Because I have a lot of people that follow me that disagree with me, they ask me questions about issues we might disagree with and I’ll explain it on the spot. It’s been pretty productive,” Elise said.

Elise added that she makes resources for others to educate themselves, such as an 18 page document containing a list of Trump’s “failures and unkept promises,” which she shares through social media. Many students, such as Roo, don’t create such resources themselves, but rather amplify them by reposting links and posts on Instagram, among other social media platforms.

“Whenever civic education includes topics that may be

controversial due to political beliefs or other influences,

instruction shall be presented in a balanced manner that

does not promote any particular viewpoint. Students

shall not be discriminated against for expressing their

ideas and opinions and shall be encouraged to respect

different points of view.”

MVLA Board Civic Education Policy

In the Classroom

According to Hancock, the public education system in the United States was created to reinforce and support democracy.

“The most important thing a society does is educate its young,” Hancock said. “I’m here to help you be stronger, better thinkers, and consider your beliefs and ideas so that when you go out into the world, you’re more thoughtful, stronger, better citizens, voters, and consumers.”

California Education Code (Ed Code) allows students freedom of speech to discuss politics, and restricts teachers from “influencing” students’ political views, according to Principal Michael Jimenez.

He said that as long as teachers are following Ed Code, they are allowed to disclose their political views and discuss politics in the classroom.

“You can put out facts, as long as you aren’t using those facts to get students to think… in a certain way,” Jimenez said. “[Students] have the right to learn and grow the way they want to, and believe what they want to believe.”

Biology teacher David Cmaylo said that he thinks that politics “definitely have a place” in government and social studies classes, and that he would never condemn another teacher for sharing their political views in the classroom. However, Cmaylo said that as a biology teacher, he doesn’t like to directly share his views.

“As a position of authority… I don’t want to influence [students’] thought,” Cmaylo said. “I just want them to think logically.”

Cmaylo said he is still open to hosting discussions on controversial topics in his classroom. When students discuss climate change, for example, Cmaylo said he encourages them to look at the information they are being presented with on a deeper level.

“I encourage students to look at the source of the information. Is it somebody from the oil industry, someone trying to sell you a particular point of view for a particular reason?” Cmaylo said. “I think the key is to encourage students, give students the tools to be able to think critically, and let students make their own decisions.”

Jimenez said that it’s often hard to distinguish between politics and current events.

“Anything can be political,” Jimenez said. “The big issues—climate change, race, gender equity, religion—all those things are very political. Could I draw a line between [these things] and politics? No.”

“You could put up a Black Lives Matter sign. It’s political, but it’s in support of human rights.”

Senior Enola Talbert said that she “loved” having teachers share their political opinions in the classroom because it gave her a way to know “who to trust.”

“If I had a teacher who was an open Trump supporter, I would want to know because of what [values] that person aligns with,” Talbert said. “There are certain things you don’t want to discuss with people like that.”

While Jimenez said that he could not draw a line between politics and human rights, he said the “safe space” posters that many teachers have on their classroom windows are acceptable. He said he is not aware of any issues students have with the signs.

“You could put up a Black Lives Matter sign. It’s political, but it’s in support of human rights,” Jimenez said.“The goal is to make sure that kids are feeling comfortable at school, and that they want to come here because they feel safe and they want to learn.”

Talbert said the posters are “warm and welcoming to students who might have their rights on the line,” referencing the 2020 election. Because they supported intrinsic characteristics of people, Talbert said, the posters shouldn’t be a political matter.

“If it’s part of a person, why is that a political thing?” Talbert, who identifies as black and as a member of the LGBTQ+ community, said. “My right to exist and not be killed should not be a political issue.”

Teachers Cmaylo and Hancock both believe it is appropriate for teachers to recognize human rights.

Hancock said that when violent and traumatic events such as school shootings occur, she tries to make the classroom a place where students can explore and discuss them. She mentioned the Brett Kavanaugh confirmation hearings, specifically the testimony that Christine Blasey Ford gave accusing Kavanaugh, a current Supreme Court justice, of sexual assault.

“If we have something like… the confirmation hearings happen, and teachers just come into the room and say, ‘we don’t have time because we have to take a quiz’, then that sends the message to you guys that this doesn’t matter that much,” Hancock said.

Despite her efforts toward making the classroom a place where all students can contribute their political opinions, Hancock said that she has had conservative students approach her after in-class discussions with concerns about sharing their viewpoints in class.

Hancock said that such students often worry that their opinions aren’t “right.”

“It’s genuinely a problem,” Hancock said. “I would love to figure out how to make our community more respectful and safe for our students who are conservative… It’s not okay that those students don’t feel heard.”

Zhang expressed a similar sentiment.

“In classes like U.S. history where current events are brought up in class, the teacher will often narrate the story from the Democratic or leftist perspective,” Zhang said. “That does make me doubtful to express my views, not knowing what the impact will be.”

“My right to exist and not to be killed should not be a political issue”

Similarly, Poh said she has had teachers who openly and regularly criticize Trump. She said it makes her feel uncomfortable and frustrated because she believes teachers, as authority figures, should not be pushing their political agendas on students.

Hancock said that sometimes conservative students feel so frustrated about being shut out they default to saying provocative things in discussions.

“I don’t blame them,” Hancock said. “If you feel like your voice is being shut down and shut out all the time, then at some point you’re going to be like, ‘whatever, I’m going to say whatever I want to say, and what are you going to do about it?’.”

Despite the dominant liberal perspective in the community, Hancock said she strives to impartially educate.

“I think that one thing we can do as staff and adults is be mindful… that we respect and honor differing perspectives, as long as those perspectives are respecting and honoring all people as well,” Hancock said.