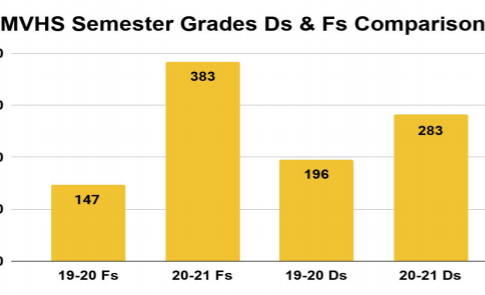

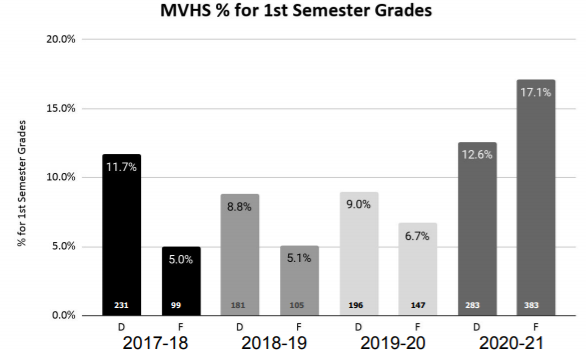

The number of Fs students received at the end of last semester has more than doubled compared to the number they received in the first semester of the 2019-2020 school year.

At the Jan. 25 district board meeting, Distance Learning Administrator Teri Faught presented statistics that showed the number of Fs that MVHS teachers gave students rose from 147 to 383, a 10.4 percent increase in terms of all the grades given in the first semester last year to this year. The number of Ds rose from 196 to 283, a 3.6 percent increase.

At the quarter mark, according to Faught, the effects of distance learning were showing in the high number of failing grades. Statistics presented at that same board meeting showed the number of Ds was at 614 and the number of Fs was at 611.

“We saw that distance learning was going to pose challenges, and that that would probably result with a few more Ds and Fs,” Faught said.

In order to meet those challenges, the board discussed students’ technology, the schedule, and teacher training, according to Faught. As a result of these discussions, the administration added more Zoom classes from the distance learning portion of the spring semester of the 2019-2020 school year to increase engagement.

Teachers had several days of training to learn new skills and techniques to use in synchronous Zoom classes, such as manipulating break out rooms and chunking, and also skills to keep up engagement, such as talk time and motivation boosting.

“We did [professional learning days] through the lens of engagement and motivation and connection and building culture and supporting grades,” Faught said.

According to English Teacher Esther Wu, more than 50 percent of Ds and Fs came from Latino students, specifically English language learners and those who are economically disadvantaged.

We’re seeing the impact of being in distance learning on [English language learners and economically disadvantaged students] in particular.

“It seems like the system has created more barriers for [English language learners and economically disadvantaged students],” Wu said, “We’re seeing the impact of being in distance learning on those communities of students in particular.”

Even with training and preparation, Wu said that the technical issues of distance learning often make it difficult for teachers to control student engagement.

“That’s the biggest change that I see from last year. Our students who would really benefit from being on campus, from having stable Wi-Fi, or from going to the textbook center if their Chromebook blows out; they don’t have that anymore,” Wu said.

“It is quite hard to learn, or even follow along with a class when you can only hear every fifth word a teacher says,” Wu said. “A student may miss a teacher’s cue to go to Canvas and open a document or watch a video. Then a student is far behind the rest of the class and there is nothing they can do about it.”

AVID and Science Teacher Kim Rogers said she has students that come in and out of her Zoom class three or four times a period because their Wi-Fi suddenly stops working, kicking them out of the meeting.

“You can imagine trying to piece together a lesson when you’re missing chunks of it,” Rogers said.

Wu said that “distance learning speaks to a very specific type of learner,” because a level of tech savvy is needed to navigate Canvas, Classroom, and Zoom at the same time, and you have to have the ability to focus on your screen for 75 minutes at a time. According to Wu, distance learning, “draws upon a very specific skill set which is not necessarily a strength for everybody.”

According to Rogers, students are meant to learn in a classroom, not “isolated and interacting via a computer.”

With this transfer of learning from the classroom to computers, traditional grades no longer reflect classroom learning, according to Wu. A push towards being open to many different creative alternative ways to demonstrate the learning that goes beyond traditional pen and paper is necessary.

“Grades need to represent what a student knows and understands. If the student doesn’t have access to the classroom then they can’t demonstrate what they understand,” Rogers said.

According to Rogers, teachers started out the 2020-2021 school year with this realization in mind, cutting down their curriculum and redesigning assessments. Several course teams looked at what evidence students would need to show to demonstrate mastery, and based their changes on that.

Sometimes we can get really stuck in thinking about grades in a very traditional way that works for in-person school, but we’re not in person.

“Sometimes we can get really stuck in thinking about grades in a very traditional way that works for in-person school, but we’re not in person,” Wu said, “I think that demands a paradigm shift.”

According to Rogers, even though students are doing their best in distance learning and the school is providing many resources for support, there are some challenges that cannot be overcome online.

“There are some things that are happening that we’ll only be able to address once we can get kids back on campus,” Rogers said.

Select cohorts of students were brought back last semester, but the school cannot bring back any more cohorts until Santa Clara County enters the red tier of COVID-19 cases.

Over 60% of students reported feeling less motivated during distance learning than in-person learning in a survey given to students by administration. According to Wu, completing one semester of distance learning is an accomplishment.

“We muddled through. We learned some new stuff. And we did the best that we could with what we had,” Wu said. “For that I am really proud of our students.”