In high school, when his peers went home or out with their friends after class, substitute teacher David Alvino Hernandez Ortiz went to the library to study. He worked until closing time, then continued studying at the public park. When the lamps lining the streets switched off at 10 p.m., he went to the local McDonald’s and studied until midnight before he went to wherever he was going to sleep that night.

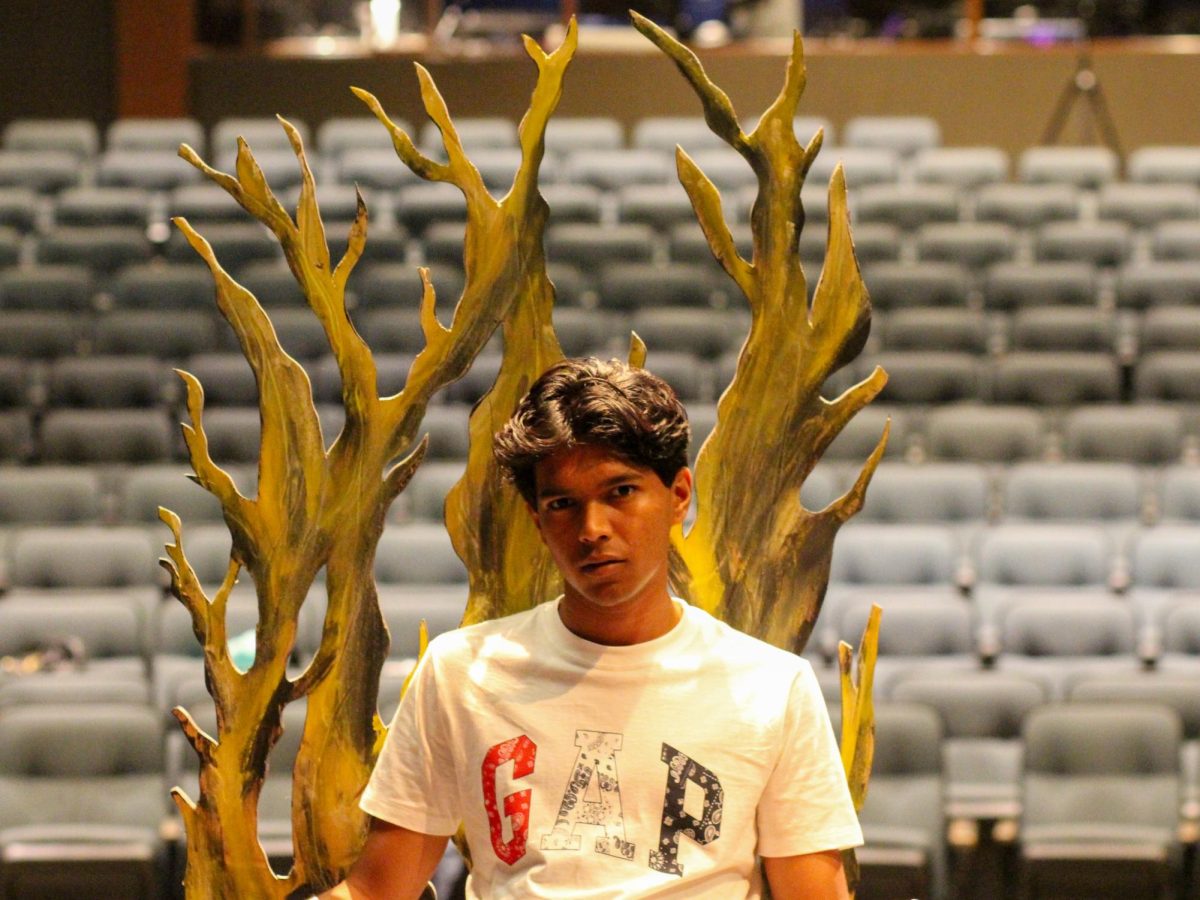

Ortiz is currently the long term substitute for Brook Mangin and is teaching her World History AP and Survey World History classes this semester.

He said that it was partially his tenacity that brought him to teach at Mountain View; he wanted to find a district that had the same standard of excellence that he held himself to.

“I like high standards, especially if they’re hard to attain,” Ortiz said. “What’s the point of something being easy?”

Ortiz’s passion for education and drive for excellence wasn’t inherent. He grew up in Bakersfield to a deaf and mute mother. Nobody in his family had achieved higher education; his mother didn’t graduate high school, and his grandmother, who raised him, didn’t complete the fourth grade.

Ortiz said that he grew up surrounded by poverty in a turbulent household. His early years were filled with violence and abuse. “I was a single child growing up in a silent world,” Ortiz said.

“I was a single child growing up in a silent world”

But he did find solace in one person: his grandmother, who Ortiz said was the only source of love he got.

“She remains, to this day, probably the most significant person in my life,” Ortiz said. “I mean, for some reason, we all have really great relationships with our grandmothers. That’s how it was with her. She gave me the impetus to really push forward.”

But in 1994, when Ortiz was in middle school, he lost his grandmother due to natural causes. He said that it was a major loss for him, so he began looking for another connection to fill the void she left. He found it in a street gang.

“I figured strength in numbers, so they became the brotherhood I was looking for,” Ortiz said. He described his gang as a sort of surrogate family.

“Growing up [an only child], I never had brothers or sisters, so to me it was more like a brotherhood. You just wanted friends. You just wanted people that wouldn’t pick on you.”

“You just wanted friends. You just wanted people that wouldn’t pick on you.”

But when he entered high school, Ortiz decided that his main focus was to get into college. He had always been smart, but he decided that it was time to focus.

“We live in a country that has a lot of opportunity where you can capitalize on it, and so I did,” Ortiz said. “I went to school full-time, that was my ticket out of there. I didn’t want to be poor all my life.”

He worked hard on his academics, and stopped talking to his ‘gangster friends.’ He took all the AP classes he could and did well in them. But the summer before junior year, Ortiz’s mother got married. He didn’t get along with his stepfather, and was kicked out of his house, becoming homeless.

“I’m asked what the scariest moment of my life was… it was realizing I had nowhere to go,” Ortiz said.

Ortiz described feeling desperate, depressed, and lonely as he lived on the streets, but said he refused to give up on his dream of education.

“I learned that if you want something, you go get it.”

“To me it never seemed that you should allow external factors to affect you,” Ortiz said. “No matter what, you can always get something if you want it. I learned that if you want something, you go get it.”

Ortiz attributes his success to the chip on his shoulder. “I wanted to go into every single AP class and make them all look foolish,” Ortiz said. “Like, you have the two parents, you have the big house, you have the car, you have the Christmas presents, but I got the grade. I set the curve, I run this class.”

He recalls that he would sit in the back of the class on purpose so that when it came time for the students to pass their assignments to the front, everybody in front of him could see his ornate handwriting. “That’s how much malice I had. Because I wanted everybody to see, like, ‘this is better than you.’ And that was that chip on my shoulder,” Ortiz said.

Ortiz graduated high school with a 4.8 GPA and a 1600 SAT and decided to go to college at the University of Southern California.

“It [USC] was different, because this was probably the first time that I was in such a diverse population with people so similar to me: driven over-achievers,” Ortiz said. He said that he got his first taste of ‘school spirit’ there; he was a football fan, and this was the first time that he was able to go to a stadium.

He originally entered as a history major. “Historical fiction kicked [my love of history] off for me, so history was one of my favorite subjects,” Ortiz said. “I love learning about battles, and military history, and important figures, and the civil rights movement, the Chicano movement.”

This interest in history prompted him to pursue a degree in anthropology and archaeology. “You understand that people might not live on forever, but architecture lives on forever,” Ortiz said of his fascination with ancient structures such as the Pyramids of Giza, the Karnak Temple Complex, and Chichén Itzá.

After graduating from USC, Ortiz decided to join the military. “I graduated from a prominent university, that’s great, but I didn’t have the family type atmosphere,” Ortiz said. “I was still looking for that missing piece.” He was inspired to join mainly by his uncle who he said took, “great pride in the military.”

Ortiz was an infantryman and served for three years. He was deployed in Afghanistan for 8 months, during which time he was involved in combat. While there were some parts where he had to, as he said, “embrace the suck,” he described it as an overall positive experience, with the best part being the camaraderie he shared with all of his “brothers and sisters”.

“I don’t think there’s an environment that’s more equal than being in the military,” said Ortiz. “Besides the rank that separates you, the only color we really see each other in is green. Overseas, people don’t differentiate you based on color, sex, gender. They look at that flag and they say you’re American.”

After serving for 5 years, Ortiz returned home and taught for three years in multiple cities. “It’s like a therapy for me,” Ortiz said. “Because as a veteran, you want to be useful, you want to contribute to society, you want to make society better somehow. There’s no better role where I can write my own history in, so that way you can go on to the world and contribute at a greater pace.”

While he enjoys teaching, Ortiz also wants to continue furthering his education. When he isn’t teaching, grading, or making lesson plans, he is pursuing his graduate degree in Learning, Design and Technology and Curriculum Studies and Teacher Education at Stanford, a lifelong goal of his.

“A lot of my ancestors came here looking for a better future,” Ortiz said. “And when they came here, they knew that they probably couldn’t do better for themselves, they probably could only get what they could get. But at the same time there was a gleam in their eye, and that gleam was us. We were their dream. And that’s probably the reason why they call some of my brothers and sisters dreamers – because we were the dream.”

“That’s probably the reason why they call some of my brothers and sisters dreamers – because we were the dream.”

But Ortiz doesn’t see himself quitting teaching anytime soon. He said he thinks that the solutions to the world’s problems exist within the classroom, and that he wants to be a part of helping produce the world’s future problem-solvers.

“We as teachers want to see everyone be successful,” Ortiz said. “We want them to be productive, we want them to be progressive, we want them to be able to hold a conversation, be able to you know raise a family, be prosperous, get all their dreams accomplished. In return, our biggest accomplishments are you guys. Regardless of the pieces of paper we put on the wall, regardless of the titles we carry, regardless of the money we make, the houses we have, the cars we own, whatever might be our greatest accomplishments will always be you guys.”