Gentrification in Mountain View

The Silicon Valley’s booming technology industry has brought higher-income developers, designers and techies to the area. These new companies and residents funnel more money into our local economy, setting off a chain of both positive and negative effects.

While a more affluent Mountain View community could have higher-ranking schools and cleaner streets, the change could diminish Mountain View’s diversity by driving out lower-income residents.

Of low-income households in the Bay Area, 53 percent are at risk of displacement, as reported in 2013. Median rent has increased 54 percent from 2011 to 2015, and is currently $4,150 per month. If rent prices continue to increase at such a rate, a greater number of residents will be forced to leave the community.

As a result, rent control has been a significant topic of discussion in Mountain View that has appeared consistently on City Council agendas and has incited protests by groups like the Mountain View Tenant’s Coalition, which advocates for rent control.

Within our school community

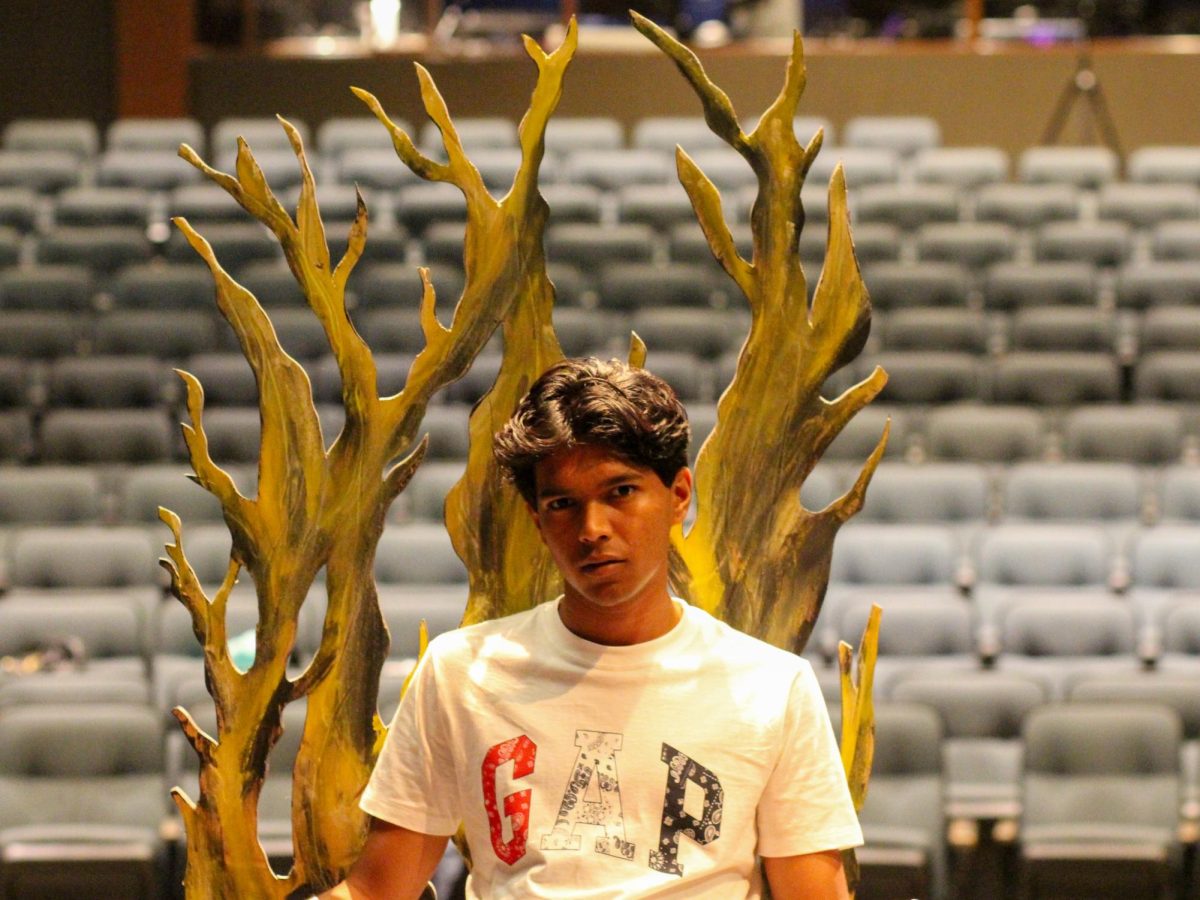

Junior Christina Vasquez had already moved three times before coming to Mountain View in middle school. Because of increasing rent prices, she and her family have lived in six houses, and Vasquez is currently attending her seventh school. A week before her junior year, the landlord emailed her family to inform them that their rent would be raised again–12 percent in upcoming months.

Japanese teacher Nicole Higley has also faced financial difficulties. Four years ago, she moved to the Bay Area from Japan, looking for housing close to the school.

At the time, math teacher Evan Smith was also looking for housing. Opting to become roommates, he and Higley rented a two-bedroom apartment in Mountain View for $2,495 a month. Currently, Higley is in the process of moving into an apartment with her partner. The apartment is 300 square feet–a high school basketball court is 4,200 square feet–and will cost $1,800 a month. Because of rent prices, she does not plan on making Mountain View her permanent home.

“I can barely, by living paycheck to paycheck, live on my own,” Higley said.

Like Higley, Vasquez faced rising rent prices, yet thrived in the MVHS community. She joined choir and AVID (a program designed to prepare first generation college students for college), made many friends, and formed close relationships with her teachers. At the end of sophomore year, she auditioned and was chosen to be a part of Madrigals, the highest level singing group on campus. However, when her family received an email from their landlord, they had no choice but to leave.

“We were already struggling, and they were going to [raise the rent] again, so we had no choice,” Vasquez said. “There were nights where we didn’t know where to put our money or where to save it–is it more important to have food today or is it more important to have movers?”

Vasquez was willing to make the hour-long commute, but the district denied her parents’ request for her to stay at MVHS. The family left Mountain View within two weeks; the move was so sudden that Vasquez missed the first week at her new school. She was also forced to leave behind her passion.

“It killed me when I had to leave choir because choir’s my thing. I am currently in a choir class where no one wants to be there–it’s a joke, and it’s not a good environment,” Vasquez said. “That was really, really, hard. And I had plenty of days where I cried myself to sleep, because I was not able to pursue what I wanted to pursue.”

P.E. and AVID teacher Tami Kittle has seen the effects of such financial burdens on many of her students–some work three jobs, skateboard 10 miles to and from work, or live in families with an annual income of $20,000,

well below the poverty line.

“They’re the strongest kids on campus,” Kittle said. “Kids that have to deal with the harsh of every day, but are happy and hardworking and fun and beautiful. They need to be celebrated.”

Exploring the broader effects

About 60 percent of Mountain View’s residents are renters, and tech companies like Google are increasing the competition for a significantly limited inventory of rental units.

Due to the imbalance between job growth and housing inventory, long-time middle-income residents are being displaced. This economically and socially marginalizes them, and Daniel DeBolt, communications organizer of the Mountain View Tenant’s Coalition, speculates that this will lead to racial and class tensions.

When lower-income families in Mountain View are forced to move because of rising rent prices, they tend to relocate to lower-income neighborhoods. According to a UC Berkeley research project, lower-income families are twice as likely to relocate to a more impoverished area than a more affluent one.

This is concerning because low-income neighborhoods tend to lack the quality of resources and opportunities available in middle and higher-income areas. Christina Vasquez, a former MVHS student, was forced to relocate because of rising rent prices. She moved from MVHS, which has a college readiness index of 60, to a school with a college readiness index of 30.

When a community’s working class, which includes many ethnic and racial minorities, is displaced through gentrification, they are replaced by a new wave of high-income families. The arrival of new tastes, expectations and demographics damages the social and cultural aspects of the neighborhood. This effect has been acknowledged by members of City Council.

“I fear the fabric of our city is being ripped apart in front of our eyes,” Councilman Ken Rosenberg said, regarding gentrification.

Much of this cultural change is due to the fact that, as estate and rent prices grow, many small businesses can’t survive.

The Mountain View General Store, a boutique that sold gifts, jewelry and housewares made by local artists, closed this past spring after three years of successful business. The owner stated that “the support of the store has been overwhelming, however, it’s just not enough to support living [in Mountain View].” According to DeBolt, when small coffee shops, book stores, or boutiques like the Mtn. View General Store are replaced with generic brands, it detracts from the cultural value and unity of Mountain View.

At the cost of smaller businesses and lower income residents, gentrification can be seen as a symbol of economic growth. As more money flows into Mountain View, many aspects of the community can be positively impacted.

The results of gentrification in other neighborhoods indicate that when higher-income residents move into Mountain View, more landlords will renovate old buildings. And as housing conditions improve, the neighborhood will become more visually pleasing, clean and livable.

Local public schools will benefit from the increase in funding that they will receive from the increase in property taxes. And while long-time residents can initially benefit from the cleaner streets and better schools, many will eventually be forced to move out due to the high cost of living.

Discussing potential means of providing relief

As demand for housing in Mountain View continues to rise, members of our community are discussing how we can and should control or prevent gentrification.

According to Daniel DeBolt, the communications organizer of the Mountain View Tenant’s Coalition, the question of our time is, “can we balance job growth with affordable housing?” So far, no one has proved that it’s possible.

“Every time there’s a boom in the Silicon Valley, something like six time more jobs are created than homes being built,” DeBolt said. “It’s like a compounding shortage that gets worse every time there’s a boom.”

When demand increases faster than supply, prices rise. This is the true cause of high and rising rents–not greedy landlords, but lack of housing. According to Forbes, “only 179 new housing units were built between 2010 and 2014” when Mountain View’s population grew by over 5,000 people.

The lack of building is mostly due to the obstruction of new construction by local governments and their residents. The supply cannot keep up with the demand to live in places like Mountain View that have job growth. To combat this shortage, DeBolt suggested Mountain View implement policies that restrict office growth unless it correlates with commensurate housing growth.

Such a measure would require companies like Google and Facebook to ensure an adequate number of homes are built while their offices are expanding. City Council has not discussed holding major tech companies accountable for taking precautionary measures, like building housing on their property, as a condition for office growth.

“City councils are scared to strongly advocate that way because they’re scared that a company like Google would leave and go to another city,” DeBolt said.

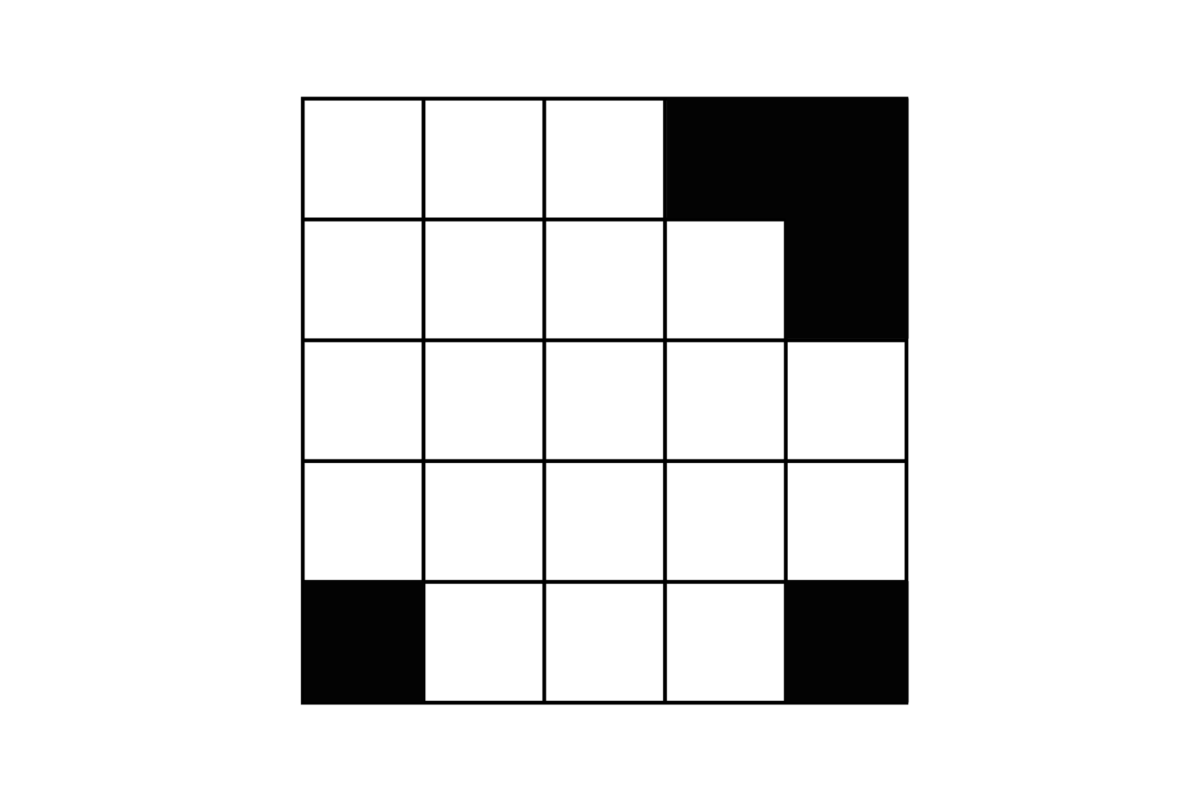

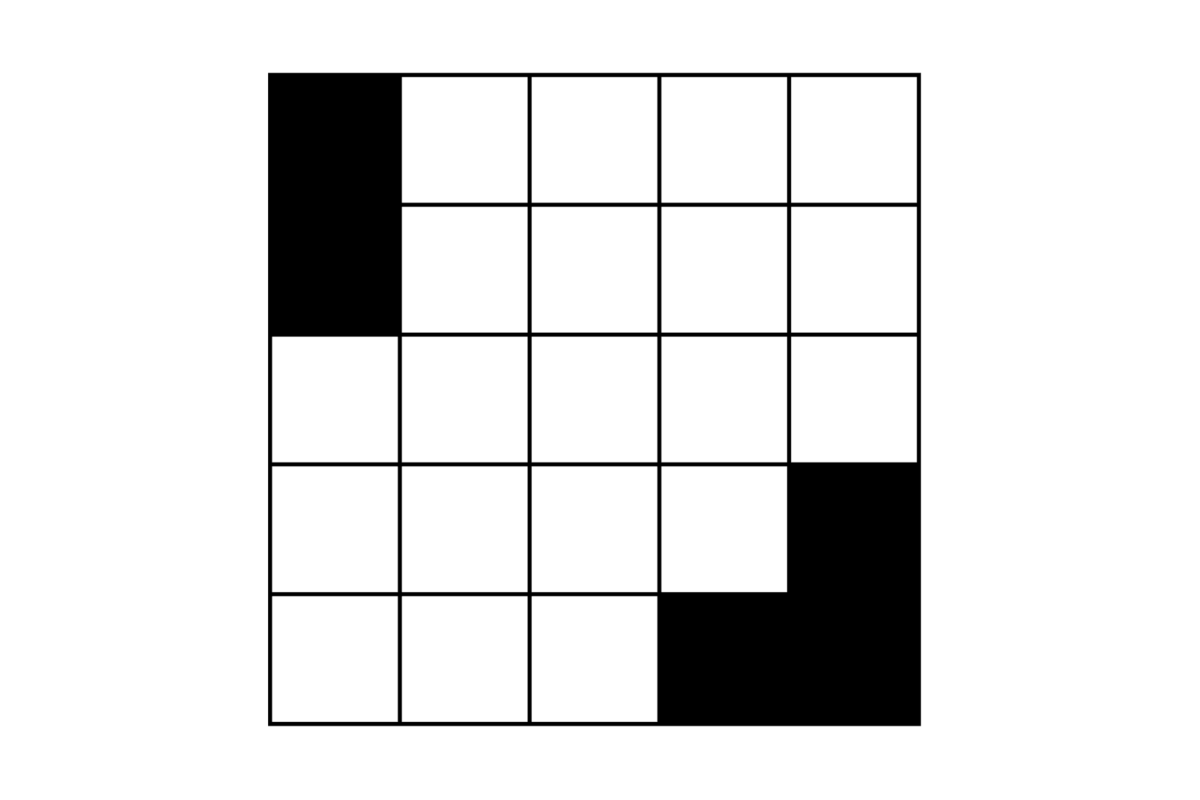

Further, many individuals argue that the best way to address gentrification is by setting price controls and limits on rent increases. The MV Tenants Coalition succeeded at getting its proposal, Measure V, on the November ballot.

According to Councilman Michael Kasperzak, the majority of the council disagrees with the principle of rent control and is opposed to the Coalition’s proposal. Soon after the Coalition’s proposal qualified for the ballot, City Council drafted Measure W, an alternative to Measure V, to appear on the same ballot. (refer to table for more info on Measure V and Measure W).

Juliet Brodie, director of the Stanford Community Law Clinic, helped draft Measure V but acknowledges that rent control has shortcomings. Although rent control may seem effective to tenants at the moment, it lowers the incentive for builders to construct more rental housing, which would be a longer-lasting solution.