On her first day of first grade, senior Sarah Jung saw a classmate beaten by her teacher. Witnessing physical punishment like this was typical of her experience in the South Korean education system, she said.

“My teacher smacks this kid across the face and he falls over. She uses him as an example,” Jung said. “She does that to him because he lives with his grandmother in the rural area, and he doesn’t have a lot of financial power.”

When Jung told her mother about the incident, she attempted to rally support from other parents and have the teacher fired. However, Jung said, the other parents advised Jung’s mother against taking action, instead telling her to offer the teacher extra pay, as they did, to ensure that she wouldn’t physically punish Jung.

Jung immigrated from Korea on Oct. 30, 2008, partly because of her parents’ work, but also to escape a “broken” education system. South Korea has one of the highest suicide rates in the world, a statistic Jung attributes largely to academic stress.

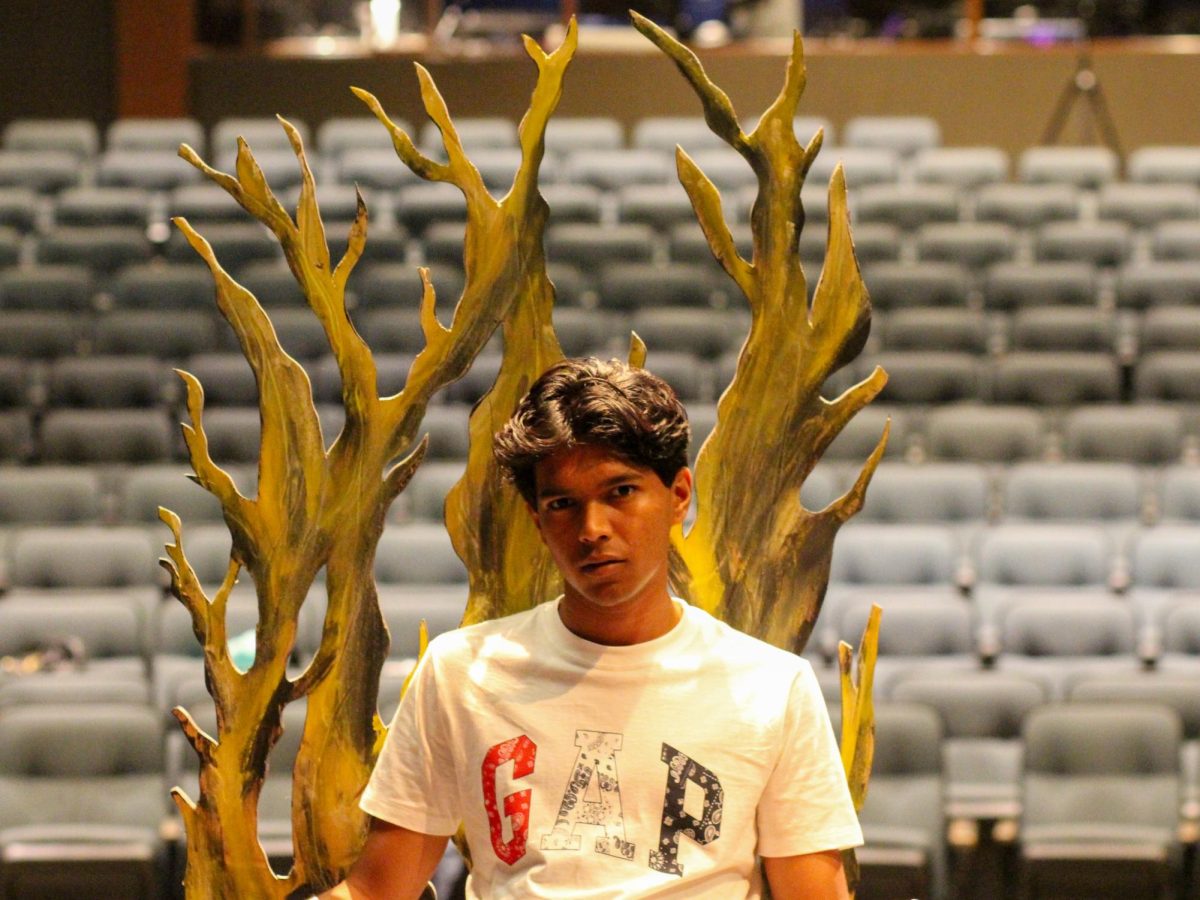

Like Jung, junior Luke Lee is an immigrant from South Korea. He came to America last year in September for his parents’ work, and he also associates education in South Korea with heightened pressure.

“It is intense,” Lee said. “There’s no retakes. You know everyone in you classroom, you take the same test, in the same class, on the same day.”

Lee expects to return to Korea. Jung, despite the fact that she loves visiting — who doesn’t love Korean spa? — has no plans to return to Korea as a permanent resident.

“I have very different values from Korean values,” Jung said. “[Korea is] a lot more traditional. There’s a distinguished hierarchy, and I don’t believe in that. I could not see myself able to work or raise my children in Korea.”

Because of this divergence of values, Jung is hesitant to call herself Korean-American, but admits that she sometimes feels she “belongs less in Korea than [she] does in America.”

According to Jung, Korean culture has changed enormously since she moved, from slang to street style to K-pop’s growing international reach.

“Korean culture has changed so much, and it continues to change without me,” Jung said. “The only part of the culture I get is media.”

Jung still reads Korean cartoons and watches Korean dramas, and her sister is a huge K-pop fan. However, Jung said these links to Korean culture are “very limited.”

As a part of having lived in South Korea, both Jung and Lee have distinct insight on the relationship between South and North Korea that may differ from that of the average American.

While North Korea is often perceived as an enemy to South Korea, Jung’s sees the two as one country with a shared heritage. She said that the Korean people, separated by a “corrupt North Korean government,” still want to be reunited.

Therefore, when threats of nuclear war are flung across the Pacific, she’s ever-aware that South Korea will be affected, too.

“Not just because of proximity, but because we are one people,” Jung said “Our people, our land, our history will all be destroyed.”

Similarly to Jung, Lee’s view of North Korea is complex. He said he “hates” the government, but tries not to hate the North Korean people.

“It’s not fair to hate America for Donald Trump, and it’s not fair to hate North Korea for that pig,” Jung said. “A lot of people don’t make the distinction between North Korean government and North Korean people. Those people are brainwashed. There are daily executions that they are forced to watch. They get executed for watching Hollywood movies. They get executed for listening to K-pop.”

Zohaib Hasan • Nov 23, 2017 at 10:28 pm

Good country for education